‘The nineteenth century is nothing if it is not critical. Nothing escapes. The most precious beliefs and the most benevolent institutions have to undergo the ordeal’

The Lancet, 1881

By 1860 all the great general hospitals had been founded and the basic structure of the metropolitan hospital system was well established. Some earlier difficulties were on the way to solution. Nepotism was far less blatant and the establishment of the General Medical Council had provided the profession with a new stability. Yet the decade of the sixties was a period of rapid political change, indeed political unrest. The debates about education and the franchise, like those about Poor Law reform, were national in character. Advances in science — the publication of The Origin of Species is often quoted — and in medical specialisation posed problems for hospitals throughout the country. Other issues were essentially metropolitan, for the rising population and the pattern of growth of London increasingly revealed the inappropriate locations of hospitals. There was no consensus about the nature, let alone the solution, of many of the difficulties; for example the basis on which patients were selected for admission, the way to finance the hospitals, or questions of governance and authority. No easy solutions were to emerge in the next thirty years, but the many interests involved and the constraints within which the hospitals worked became more clearly defined.

In 1862 The Lancet reviewed the expansion south of the Thames.

‘In 1745 — subsequently to the foundation of Guy’s — only a narrow strip stretching a little way above and below London Bridge was built upon. In 1818 this area was about doubled. In 1834 the area of 1818 was doubled; and in 1857 the inhabited area had doubled again. A dense population had stretched below Greenwich, as high as Battersea, and far to the south. Still, for a hundred years, no new hospital had been erected.’

The hospital accommodation for south London amounted to 1,130 beds for an area of 70 square miles and a census population of 773,000. Further, the counties of Surrey and Kent sent ‘large contingents to the crowds of sick and maimed who throng the gates of the two hospitals at the foot of London Bridge’.’ The Lancet contrasted this pressure with the services enjoyed by the more fortunate population on the north of the Thames. Here, in fifty square miles were 2,000,000 people, twelve hospitals, at least 2,656 beds and the vast majority of the special hospitals. Philanthropy had been lavish in the north with 70 beds per square mile, one for every 536 inhabitants. The south housed a larger proportion of the ‘labouring population’ and had 16 beds per square mile, one bed to every 700 inhabitants.

The removal of St Thomas’s Hospital

The buildings of the old St Thomas’s Hospital in Southwark had been known to be substandard for many years. When the government proposed to move its offices from Somerset House in the 1830s it was suggested that the hospital should move into the building in conjunction with King’s College. The medical staff themselves wrote to the governors in 1832 suggesting that the hospital should be rebuilt ‘in a more eligible situation’ to promote the benevolent views of the founder and the supporters. The staff pointed to the ‘decayed state of the existing hospital, the great improvements in hospital design, the growth of London which required a more equitable distribution of hospitals, the increased accommodation at Guy’s, and the notoriously smaller number and less urgent importance of cases applying for admission now than formerly.’2 The development of the Greenwich Railway from 1837 onwards posed a more direct threat to the hospital’s site, and the problem became acute in 1859 for the rails were going to cut across it passing fifteen feet above ground level within a yard or two of the wards. The disputes which followed brought problems facing the hospitals to public attention. A threat concentrates the mind and many beliefs were re-examined: the sanitary and professional arguments for the town or country location of hospitals; geographical distribution within London; the objectives of the medical charities; and the influence doctors should have on the hospitals’ governors.

When it became clear that the extension of the railway might force St Thomas’s to move, an influential group which included the treasurer and many of the governors favoured relocation in an accessible London suburb to the east. There might be an experiment ‘collecting the sick at a receiving house and sending them for treatment as soon as they could be moved into the pure air of the country’.3 The resident medical officer, Mr R G Whitfield, the third of his family to hold this post, favoured this course of action. He believed that the new forms of transport and the changes in the distribution of the population could not be ignored. The population of Greenwich and Lewisham was increasing more than any district south of the Thames, whilst in some parishes in Southwark the population was falling. He argued that the locale of the poor would alter and they must emigrate from necessity, just as the rich had done from choice. He thought that parents would sooner send their sons to a medical school in a neighbourhood more savoury than Southwark and that as most medical treatment was carried out by resident staff a short train journey for visiting staff would prove no hardship.

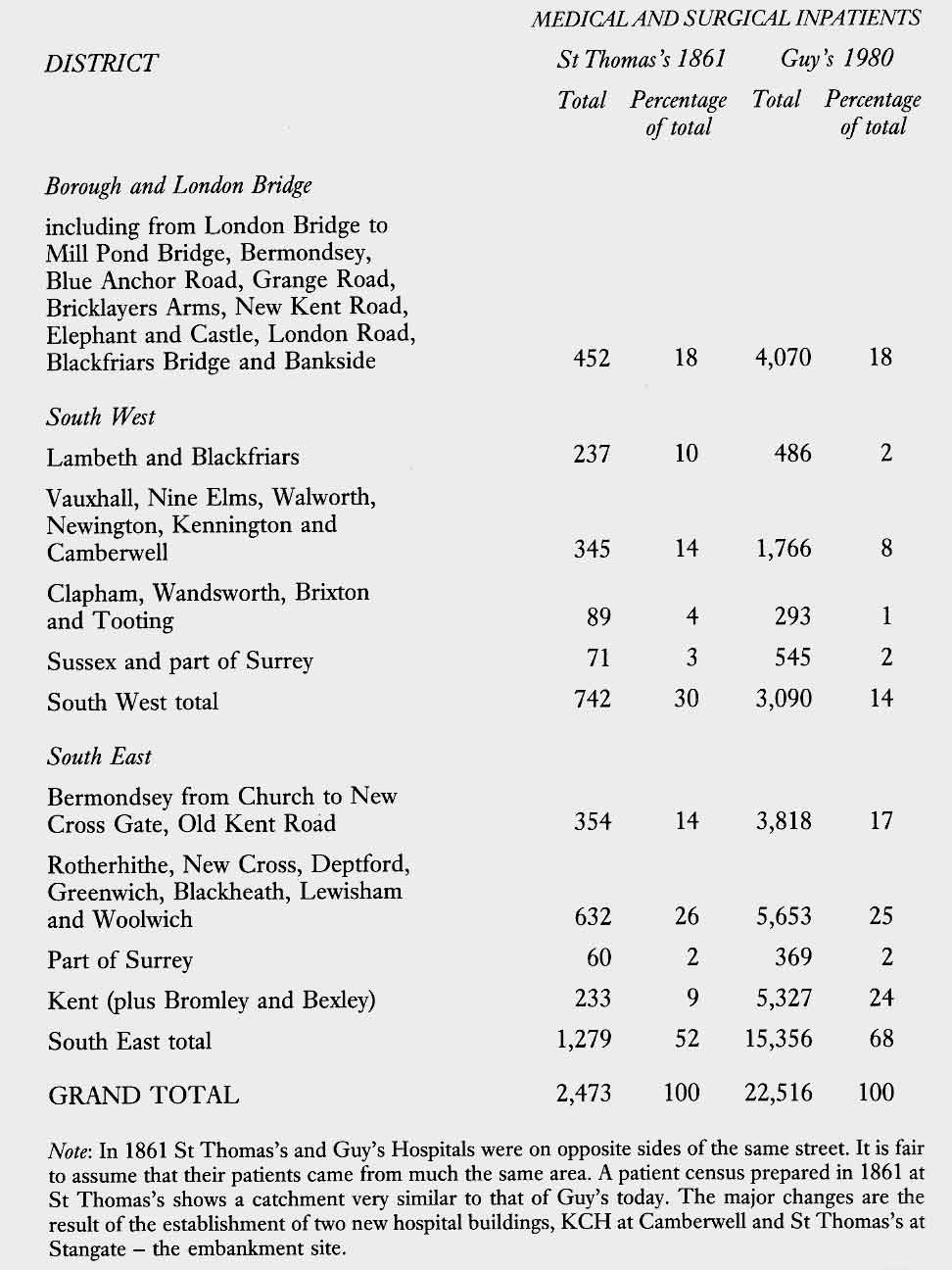

Whitfield had two campaigns to fight, first to ensure the sale of the whole site, so that the hospital obtained the maximum compensation from the railway company, and secondly to achieve relocation outside London in the country. Distrustful of the motives of the visiting staff, he was at times in almost daily communication with Miss Nightingale, who had a freedom of action which he did not enjoy. Miss Nightingale wrote to him that there was an opportunity to build the finest hospital in the world, but that if St Thomas’s stayed in Southwark it could be no fit place for training nurses. Whitfield replied that he wished he could whisper in Prince Albert’s ear that the prince should interest himself in the debate, and its sanitary importance.4 Shortly after, in March 1859, the prince spoke to the treasurer on the subject, and he wrote formally to the governors. Whitfield obtained the admission tickets of accident cases from the steward, analysed the patients’ addresses showing that many came from places some way to the south-east, like New Cross, and provided Miss Nightingale with the figures. A few days later the analysis appeared in The Builder, a journal on cordial terms with Miss Nightingale, to support the case for removal to the east. The analysis, when repeated 120 years later, shows how little change has taken place in the origin of patients seen in St Thomas Street, Southwark.

In July 1859 Whitfield took a convalescent holiday in Paris and wrote copious reports to Miss Nightingale about the ventilation and sanitation of the hospitals at Lariboisière and Vincennes.4 Florence Nightingale opposed the construction of hospitals in towns on sanitary grounds and believed that while special wards might be needed centrally for accident cases and sudden illness, patients should be sent on to suburban hospitals as soon as they were fit to make the journey. A wider distribution would not only make hospitals healthier, but would improve their accessibility to patients.5 The medical press took different sides in the dispute. The Lancet favoured central location, whilst the Medical Times and Gazette believed that the benefits of removing St Thomas’s from the Borough to a healthy situation in the country, with its pure and invigorating air, would outweigh the inconveniences.

Changes in patient flow patterns, 1861 - 1980

The medical staff at St Thomas’ did not share Whitfield’s views. The governors were bombarded with printed leaflets for the best part of a year. After discussion with Miss Nightingale, Whitfield organised a survey of patients which showed that more came from the south-east than from the ‘home district’ or from the south-west. The south-west seemed a poor place to be in any case, for ‘numerous unhealthy factories saturated the atmosphere with their noxious products making the place perfectly unsuitable for a hospital’. Each governor received an attractively coloured map of South London and statistics of patient flow purporting to show that the main catchment of St Thomas’s was to the south-east. They were presented in a way designed to lead to the conclusion Mr Whitfield favoured.8

John Simon and the medical staff remained opposed to a move and Whitfield was forced onto the defensive, saying that he was convinced that ‘by the close of the present century succeeding generations would do full justice to his opinions’.9 A decision was delayed until the last moment and when the purchase price of the site had been settled by arbitration at £296,000, the hospital had to find a new home as a matter of urgency. Many possibilities were examined, some of which were unsuitably sited near factories and knackers’ yards. Ultimately the governors took a lease on the old Surrey Music Hall in Surrey Gardens, off the Walworth Road immediately to the south of the Elephant and Castle. The old buildings were rapidly converted and this, like the removal, went smoothly. The capacity of St Thomas’s in its new and temporary home was greatly reduced; the buildings themselves were excellent and stood in pleasant grounds. The hospital reopened within weeks and the wards filled rapidly, confirming in the minds of many the need for a central site. Guy’s, now standing alone, came under heavy pressure.

The immediate problem had been solved but there remained a division of opinion about the ideal permanent site. The governors continued to favour relocation in the country, perhaps in Lewisham, whilst the medical staff wished to stay in London. The City of London and the local vestries were alarmed at the prospect of losing the hospital and organised a campaign to keep St Thomas’s in Southwark. The Social Science Association listened to an address in which an idyllic picture was painted of hospitals pleasantly located amidst herds of cows on the southern slopes of the Surrey hills.11 The doctors pointed to the need for the hospital to be accessible to sick and injured people, rather than cows. In their view a country site would turn the institution into a convalescent home and undermine the medical school. The staff maintained that the death rate in a hospital had little to do with the type of air it might enjoy. Country air did not of itself reduce mortality for the cause of hospital sepsis lay in the organisation of the hospital itself, not in its surroundings. In a ‘memorial’ addressed to the president, treasurer and governors of the hospital, the medical staff drew attention to the damage which would be inflicted on the hospital and medical school ‘if the new hospital were to be planted in any locality where physicians and surgeons of high metropolitan standing could not be expected to serve it with assiduous attention,'12

Throughout 1862 The Lancet ran a campaign against a country site, pouring scorn on the ‘outdated sanitary ideas of the governors' and comparing the results of English and French hospitals. Dr Bristowe, a physician at St Thomas’s, repeated the arguments in favour of a central London location when he gave the opening address of the academic year in the presence of the treasurer, and appealed for improved communications between the governors and the medical staff.13 Indeed, whilst it was quite true that the suburbs were expanding rapidly, the central boroughs south of the river were themselves desperately in need of hospital accommodation.

The governors gave in to the pressure to remain in central London. Seven sites were short-listed, one of which was the nearby Bethlem Royal Hospital which some believed should be moved into the country in the interests of the long-term residents. Surrey Gardens itself was in many ways ideal, not least because of its size and the wish of the owner to sell to St Thomas’s. Instead the governors chose the Stangate site, part of which was to be reclaimed from the Thames as the Board of Works constructed the embankment. The Lancet was not entirely happy - it seldom was - for as a riverside site it suffered from the stench of the Thames and it was not the healthiest of places. When The Lancet introduced its sanitary report on the Thames it said ‘We have a certain feeling of satisfaction that the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Mr Gladstone, has been forced to beat an ignominious retreat from the Committee Room, handkerchief to nose.’ Worst of all, the Stangate site was costly and required special foundation work. Miss Nightingale also disapproved. She wrote that the position at Westminster Bridge was ‘the worst about London, only 2 feet above the water mark’. It was ‘a place totally unfit for the sick’.15

Opposition to the Stangate site only ceased after a court case brought by the City of London in March 1864. The governors presented evidence on the healthiness of a riverside location based upon the experience of the Seamen’s Hospital, the Millbank penitentiary and the Hotel Dieu on the banks of the Seine. The court concluded that it had no reason to disturb the deliberate choice of the governors, even though Surrey Gardens was nearer to the original site of the hospital as well as being cheaper.

The governors had been to France to see Lariboisière and Florence Nightingale had been consulted about the plans. Henry Currey’s pavilion plan was settled upon and details published in The Builder and in the medical press. On 13 May 1868, with the solemnity of prayers and psalms, the clang of martial music and the roar of cannon in salutation, the Queen laid the foundation stone. The medical staff looked forward with pleasure to the great new hospital. By current standards it was vast but a system of electric communication was installed ‘to diffuse intelligence’. Some accused the governors of over-lavish expenditure16, but in general comments were favourable and Queen Victoria returned to open the hospital in 1871. The new St Thomas’s was described by the illustrated London News: ‘The range of buildings has a frontage of 1700 feet, nearly equal to the length of the Crystal Palace. The style of the architecture is Palladian, with rich facings of coloured brick and Portland stone, with carved ballustrades for the balconies.’17 The clinical accommodation provided everything necessary for the work of a great hospital. But the cost had been enormous and the building committee reported on it to the court of the governors. Neither, in spite of all the advice that had been taken, was the hospital free from the infections which its advanced sanitary design was meant to obviate. There was still much to be learned about hospital construction, hospital management and the need for fastidious cleanliness, commented The Lancet.18 There was a risk that the new hospital might be regarded as a model which could be copied with confidence.

The Westminster: reconstruction or removal?

There had been no choice for St Thomas’s, but less dramatic measures were open to other hospitals which were also in need of improvement. The Lancet believed that the alterations which had been made to St George’s, Charing Cross and St Mary’s merely proved that money spent on ‘tinkering with old buildings’ instead of partial reconstruction was money wasted. The old hospitals could not be made hygienically perfect and rebuilding on a ‘scientific plan’ would have been preferable.

The Westminster Hospital, although it had been built only forty years before, was in need of upgrading for sanitary reasons by 1877. The estimated cost £13,000 and an alternative proposal to move the hospital to Pimlico, Chelsea, Battersea or Wandsworth appeared in the newspapers. The Lancet considered the matter from the point of view of the needs of the population and examined the bed-ratios on the basis of the 1871 census. Bearing in mind the differing levels of poverty in the various areas, The Lancet did not see that a case had been established for the removal of the Westminster Hospital. Neither did the house committee of the hospital nor its chairman, Sir Rutherford Alcock. The hospital proceeded to carry out the necessary alterations, closing completely for three months. The Lancet, however, urged the governors to try to erect a new building in future which more nearly approached sanitary perfection.19

There were vast improvements in patient care between 1860 and 1890. Hospitals which had been ‘places which healthy people should avoid and sick people should shun' 20, became the best places for sick men and women to be. Ether had been introduced into the London hospitals in the first quarter of 1847. Antiseptic methods were introduced more gradually between 1870 and 1880, so gradually in fact that The Lancet: in 1875 could still question whether the improved results being obtained were due to better sanitation or Listerian methods.21 As a result of specialisation and the introduction of laboratory methods doctors could achieve far more. Lastly, there was the great improvement in nursing.

|

In no department of hospital management, said The Lancet in 1864, had there been greater improvements than in nursing.22 Steele, the medical superintendent at Guy’s, thought that the change began around 1850.23New techniques in medical practice made greater demands upon those caring for patients and ‘it was properly maintained that in every hospital the best possible system of nursing that could be devised should exist, since it was second, and second only, to having the best medical skill’. A nurse now had to be technically trained to assist doctors and, simultaneously, to perform her duties with tenderness, sympathy and kindness — for which it was necessary to raise her social and moral character.22 There were never enough nurses. To attract staff of a suitable calibre was a constant problem and Dr Elizabeth Garrett told the Social Science Association that hospitals should pay better wages and not rely on religious dedication.24 Florence Nightingale disagreed, for she believed that one did not necessarily obtain a better article merely by paying a higher price.25 Nevertheless the shortage of applicants forced hospital governors to improve conditions, employ ward-maids and scrubbers and provide better accommodation. One way to improve standards, which was widely adopted, was to appoint more ladies — or at least women with superior education - to act as ward sisters. Ladies could maintain discipline more easily, and with less show of force, but caused expenses to rise.26 Lady-sisters wanted more staff, their standards of cleanliness were higher, the wards were more frequently scrubbed and the costs for washing increased. Food costs were also higher, for ‘the sisters would suggest delicacies to those with poor appetites, until patients suffered dyspepsia from over-eating.’ Nevertheless, the British Medical Journal thought that while it was always difficult to combine cheapness with efficiency, lady-sisters were the basis of the best system of nursing yet introduced. In an attempt to improve standards, parties of governors visited each other’s hospitals. In 1864 a group from the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital visited St Thomas’s, King’s College Hospital, University College Hospital and St Bartholomew’s. They wished to transfer the better features of nursing in London to their own hospital and Mr Whitfield provided them with the instructions issued to the probationers at St Thomas’s.27 The Middlesex Hospital reviewed its nursing in 1864-5. The doctors suggested that Miss Twining might introduce the probationers of her institution, St Luke’s, but the governors, having visited other hospitals, proposed instead to appoint a lady-superintendent, build a nurses’ home, introduce a uniform, institute nurse training and make other arrangements for the menial duties to be performed. At the Westminster Hospital a committee chaired by Sir Rutherford Alcock was established in 1872 to assess the alternative systems of providing nurses and to improve the standard of the hospital’s nursing. It reported that no amount of medical skill or expenditure of money was effective in treating and curing the sick if good nursing was wanting. Without intelligent training under superior guidance good nursing could not be expected. The idea of employing a sisterhood was rejected and, liking the results produced by the Liverpool Royal Infirmary training school, Miss Elizabeth Merryweather was invited south to become matron in 1873.28 Steele, of Guy’s, believed that every major hospital would benefit from having its own training institution.28 The Nightingale Fund, though first in the field, did not escape criticism. ‘With all these efforts to provide additional trained nurses’, said The Lancet, ‘one cannot help asking “what is done with the Nightingale Fund?” It was supposed to be devoted to training hospital nurses for all our public hospitals ... We must confess to have never come across a specimen of a Nightingale nurse except in the wards of St Thomas’s.’29 By the early 1870s almost all the great London hospitals, with the exception of St Mary’s, professed to train young women as nurses.30 Yet a survey carried out in 1875 by a Nightingale nurse, Florence Lees, showed that in most of them probationers were merely placed in the wards to pick up what knowledge they could. Only at the Middlesex, the Westminster, the Royal Free and St Thomas’s was some attempt made to provide systematic training. St Thomas’s training programme was adopted by some other hospitals - like the Middlesex - but the Nightingale School was not the only pace-setter. St Bartholomew’s established its new school in 1877 and appointed a physician and surgeon as instructors, so the teaching could be both practical and systematic. Sir Dyce Duckworth, who took a particular interest in the school, delivered the inaugural lecture on ‘Sick Nursing, a Woman’s Mission’. He exhorted the nurses to be obedient, observant, cheerful and clean in their work. He did not urge total abstention on them, but suggested that nurses only drank with their meals.31 The Lancet described the two plans which had been introduced into London hospitals. One was training by sisterhoods or religious orders, as in Catholic countries on the continent and at the Protestant Kaiserswerth. By 1864 twenty six sisterhoods of this type had been established in England, one of the largest being St John’s House which provided the nursing at King’s College Hospital at a cost of £1,000 per year, and at Charing Cross. Another order, All Saints, nursed at University College Hospital. One hospital, the Prince of Wales at Tottenham, actually developed out of a Deaconesses Training Institution, established in 1868 in the Kaiserswerth tradition. Here evangelical dedication and low pay was found at its most extreme. The other approach, which The Lancet favoured, was the one in vogue at St Thomas’s, where the Nightingale Fund, which had been collected at the end of the Crimean war, had been used to establish a training school. The object of this fund was to train women thoroughly for all the practical duties of hospital nursing, to find them situations and to train those who would in future train others.22 The Nightingale School, which admitted its first probationers in 1860, had no easy time. King’s College Hospital, the London and the Royal Free were considered as a base, but the Nightingale Fund Committee eventually selected St Thomas’s for the quality of its nursing and its matron, Mrs Wardroper. Writing after her death, Florence Nightingale said that Mrs Wardroper weeded out the inefficient, morally and technically, and put her finger on some of the most flagrant blots, like night nursing. During Mrs Wardroper’s lifetime Miss Nightingale was not always so complimentary and detailed studies of the school’s history have shown that in terms of discipline and educational matters often left much to be desired. There was no immediate revolutionary improvement on the wards. For many years the school’s probationers represented only a small proportion of the hospital’s nursing staff. The best nurses, in Mrs Wardroper’s opinion, were to be obtained from amongst women of the respectable classes, who had had the benefit of a fair education, and who had been accustomed to the performance of household duties. In the search for ‘raw material’ one should go neither too high nor too low in the scale or one would be disappointed. Such ladies as possessed the gift of organisation and arrangement would prove valuable assistants as superintendents, sisters or head nurses, but to be of real use as nurses in the sick wards ladies too must qualify for the work by training for it. While the sisterhoods were necessarily restricted to one form of religious persuasion in the selection of their probationers, this sectarian exclusiveness was not allowed at the Nightingale School. Technical instruction and proper supervision was the objective. Ward teaching was considered crucial, for Miss Nightingale believed that surgical nursing could only be learned thoroughly in the wards, and that the perfection of nursing might be seen practised by the old-fashioned sister of the London hospitals.33 The Nightingale School always wanted their probationers to be considered in some senses supernumerary, so that there was time to absorb the teaching. Ward teaching was supplemented by theoretical instruction from the resident medical officer, Mr Whitfield, although he did not lecture to the nurses as often as he was supposed to. Simultaneously the probationer’s social and moral character was uplifted, at least in theory, by living in the nurses’ home. A revolutionary feature of Florence Nightingale’s plan for nurse training was the demand that the entire control of the nursing staff should be taken out of the hands of men, whether doctors, governors or chaplains, and placed in the charge of a woman, herself a trained and competent nurse. Hospital governors did not always accept the necessity for this. Female control was more important to Miss Nightingale than whether nursing was secular or controlled by a sisterhood. From Notes on Hospitals it is clear that she approved of religious nursing orders with their female heads.34 In most hospitals the nurses were controlled as to discipline, education and work by the hospital managers and the medical staff; to change this was Miss Nightingale’s fundamental aim.35 Yet Miss Nightingale did not encourage nurses to usurp the medical role, and it was made clear that the Nightingale Fund was not there to provide women with an entry to medicine. ‘The nurses are there, and solely there, to carry out the orders of the Medical and Surgical Staff... the whole organisation of discipline to which Nurses must be subjected is for the sole purpose of enabling the Nurses to carry out intelligently and faithfully such orders as constitute the whole practice of Nursing.,36 These ideas were not entirely understood by the doctors who suspected the desire for nursing autonomy. A rise in the standard of nursing was desirable, but doctors saw dangers in over-trained nurses who sought to mimic medical students or even to question doctors’ decisions. Not all nurses distinguished as clearly as Miss Nightingale did - from her sick bed - between medical and nursing duties. Nurses, remarked the editor of the British Medical Journal, should remember that they were the doctor’s hands and eyes, not his brain.37 The potential for a confusion of roles clearly existed. Steele pointed out that the syllabus of the Nightingale School, if extended somewhat, would have satisfied the medical licensing authorities only a few years previously.23 Systems of nursing Florence Nightingale had discussed the way in which nurses might be controlled by governors, doctors, a religious body or by a nursing hierarchy.34 With the exception of the hospitals contracting their nursing to a sisterhood, in most of the London hospitals the chief nurse was responsible either to the board of governors, the house governor, or the doctors.30 Braxton-Hicks, the physician-accoucheur to Guy’s, wrote in 1880 that doctors had probably not taken as much interest in the development of nursing as they should have done. He described alternative methods of nurse management by ward-based or centralised systems.38 Under the ward-based system, seen before new ideas were introduced by matrons appointed at St Bartholomew’s and The London, the probationers would pass through the general and special wards, and if they were competent they would be appointed to a particular ward where they would become a fixture. Similarly, sisters would be appointed to specific wards by the hospital authorities. While the matron might recommend dismissal if she thought fit, she did not have this power herself. As a result the ward sister was supreme in her ward, responsible to the lay management and the medical staff, the embodiment of the hospital and the support of the junior doctors. Sister and medical staff would work heartily - even affectionately - for the common good. It was a decentralised system developing the habit of self-government. Nevertheless, wrote an anonymous correspondent in the British Medical Journal, the training of nurses could be totally without method, and the nurses were often of a lower standard than the sisters. Indeed some, at Guy’s, had been recruited from the venereal disease ward, or might have illegitimate children. However, in hospitals with centralised systems the ward sister was mainly or entirely responsible to the matron or lady-superintendent who had the power of appointment or dismissal. The nursing sisterhoods at Charing Cross, University College Hospital and King’s College Hospital were an extreme form of this pattern of organisation. In these hospitals the farming out of the nursing created an empire within an empire. The matron undertook a sharp supervision over the whole of the nurses, the sister was less trusted, and, in the view of Braxton-Hicks, while the services might never fall to a very low standard they could not rise to the highest. While it might be possible to maintain tight central control in a small hospital the task was immense in one of 600—700 beds. There were other problems with the central system. The medical staff might lose influence over nursing on the wards. Nursing associations might withdraw the probationers as soon as they were proficient, putting them to private nursing for profit, and leaving the hospitals with too many young and inexperienced staff. Nothing could be done to prevent this.26 Nevertheless London’s hospitals moved slowly from the ward based to the centralised system. In some ways this was inevitable as training schemes were introduced into the hospitals. Part of the raison d’être of the Nightingale Fund at St Thomas’s was to ‘train the trainers’. But when matrons’ posts were advertised Nightingale-trained nurses did not always get the positions. Sometimes when they did they were a conspicuous failure. A new generation of matrons was bringing new ideas into the great hospitals. Mrs Thorold at the Middlesex (trained with All Saints’ at University College Hospital), Miss Liickes in 1880 (trained at the Westminster); and Miss Ethel Manson at St Bartholomew’s in 1881 (trained at the Manchester Royal) were amongst them. They did not follow St Thomas’s slavishly and each hospital differed significantly in its approach to nurse training. At St Bartholomew’s Miss Manson (later Mrs Bedford Fenwick) introduced a three year course with examinations at the end of the first and third years. A certificate of efficiency was then issued. More and more hospitals came to appreciate the advantages of a nursing staff whose training enabled them not to supplant the medical attendant, but to see how they ‘could best be subservient to him, and so to be of the greatest help to the patient’. The trouble at Guy’s Hospital policies are sometimes only discussed when there is a crisis. The various nursing systems were widely debated in the course of a conflict which followed the appointment of a new matron at Guy’s in November 1879. Miss Burt had trained with St John’s House, worked as a ward sister at Charing Cross and then became lady-superintendent at Leicester Infirmary where she reorganised the nursing. On arrival at Guy’s she rapidly introduced a number of changes without discussion with the doctors. A uniform became mandatory, jewellery was banned, feeding arrangements were altered, a new training system was established, and, worst of all, the sisters and nurses were re-allocated within the hospital every three months to broaden their experience. A number of sisters and about fifty nurses resigned, most finding new employment in the other London hospitals with little difficulty. ‘Without any premonitory symptoms’ wrote a doctor, ‘we find our nurses scattered about and our sisters leaving ... other derangements of a like kind have been startling us day by day and soon, no doubt, the system will be complete’.39 The medical staff protested to the treasurer, the governors and to the press in most intemperate terms. Matters were not improved when Margaret Lonsdale, one of the new lady probationers, wrote an article in Nineteenth Century which not only described the old nursing system in the darkest of terms, but implied that the medical staff wished to be rid of the moral restraint exercised by nurses of a higher class. Practices and experiments in which the doctors indulged were more difficult to carry out, wrote Miss Lonsdale, in the presence of a refined and intelligent woman. The doctors wrote rebuttals in the next issue of the magazine, but the indictment and imprisonment of a Guy’s nurse for the manslaughter of a patient added further fuel to the flames.40 A stream of letters and leaders in the medical and lay press throughout 1880 made the key issue plain; it was the introduction of a new element, the nurse, between the doctor and his patient. The doctors regarded the interests of the patient as synonomous with obedience to their instructions. They did not object to lady sisters; many of the existing sisters at Guy’s came from respectable or eminent families. Neither was the training of nurses objectionable if it did not get out of hand. As the British Medical Journal expressed it, ‘The doctor is responsible for his patient and the nurse must be a person who owes strict allegiance to him, who pays blind obedience to his orders as a private soldier the command of his senior officers.’41 The Lancet said it was needless to argue with nurses about their duty or to define — they must obey.42 Many of the new lady-superintendents, coming from good families, were on influential and intimate terms with the lay governors. The doctors might not be. Henry Bonham-Carter, as secretary to the Nightingale Fund, drew a distinction between the need for implicit obedience to the directions of the medical staff about the treatment of patients, and matters of discipline, behaviour and conduct ‘when nurses should be responsible to their own female head’.43 The British Medical Journal was at first more active in supporting the doctors than The Lancet. Dr Habershon, the senior physician at Guy’s, was president of the Metropolitan Counties Branch of the BMA. His presidential address, at the height of the dispute, was on ‘Nurses and Nursing’. He said that the well trained and efficient nurse was one of the profession’s most valuable assistants, but he then caricatured the problems faced by doctors confronted with nurses who were conceited, pretentious, meddlesome or officious, lethargic, obstinate, worn-out, intemperate, unsympathetic or heartless. Women who were sober and of good character should be selected, and they should be trained properly, with the provision of practical instruction. The ‘trouble at Guy’s’ reflected a general dissatisfaction of doctors with the power structure of the hospitals; the medical staff felt unable to exert the control they felt to be their right. The progressive move towards centralised systems of nursing, and the way new methods of nurse training tended to exclude medical students from their traditional role as dressers, added to their anxieties. ‘Hospitals’ said The Lancet, ‘are in a special sense medical charities. Medical aid is not a combination of medicine and nursing ... the whole charity from first to last is medical.’ As institutions wholly medical in purpose, hospitals must be under direct medical control. Medicine must be paramount and the lay governors should refrain from interfering in professional matters like the care and treatment of the sick. The matron should be strictly limited to the control of the nurses and the domestic business of the hospital; she had no place or function on the wards save to see they were cleansed and the general arrangements were in good order.42 In the view of The Lancet the root of the problem was unsatisfactory systems of management. There should always be sufficient medical men on a board of governors to ensure that the medical staff were party to every aspect of the general business of the hospital. As for the professional business that was a matter for the doctors alone. The British Medical Journal agreed: ‘The fact is that the whole government of the City hospitals will sooner or later require revision ... It is essential for the truly harmonious and effective working that medical officers should sit at the governors’ board with the lay governors.’41 What began as a dispute about nursing ended by raising deeper issues of governance. The doctors at Guy’s were forced to accept new methods and concede to the governors, but they were granted membership of a weekly management committee, and extended their influence. Similar but less dramatic conflicts arose in other hospitals. To contract a hospital’s nursing out to sisterhoods was also fraught with difficulties. The division of power between the council of the sisterhood and the hospital committee created ‘an empire within an empire’. Nurses, administrators and doctors fought with each other. In 1883 the governors of King’s College Hospital, convinced by the arguments of the medical staff, dismissed the matron. The sisters went on strike in her support. This led to a schism within St John’s House, and many of the sisters left to form a new body, the Sisterhood of St John the Divine, and later joined the Community of All Saints. King’s College Hospital finally parted company with St John’s House in 1885, its new matron, Miss Monk, having worked not only with St John’s House but in Edinburgh and at St Bartholomew’s. Charing Cross Hospital also ended its contract with St John’s House in 1889, appointing a matron from Liverpool. All Saints took over the management of St John’s House in 1886, and succeeded in obtaining the contract to nurse the Metropolitan Hospital two years later.45 They continued to work at the Metropolitan until 1895, and took their leave from University College Hospital in 1899 at the time of the rebuilding. The nurses at University College Hospital then came under the control of the hospital committee, and from amongst many applicants an ex-assistant matron from St Thomas’s was appointed as matron. The uniform was changed from the black of All Saints to dark blue, and chairs replaced benches in the nurses’ dining hall. In her annual letter to the probationers of the Nightingale School in 1872 Florence Nightingale wrote that ‘our Nursing is a thing, which unless in it we are making progress every year, every month, every week, take my word for it we are going back’. Nobody doubted that the sisterhoods had raised the standard of nursing in the hospitals with which they were associated. But later they found it difficult to make progress, and to come to terms with new developments in curative medicine and the need for improvement in nurse training. Campaigners against vivisection had a significant influence on the development of nineteenth century hospital policy. The laboratory work which provided the foundation for a scientific approach to medicine included work with animals. Such studies made more headway on the continent than in England during the earlier part of the century. Only in 1849 did the house committee of The London Hospital agree to a request from the medical staff for the purchase of a microscope. Harrowing accounts of operations on live unanaesthetised animals, published by the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, dealt with events in France.46In the next twenty years scientific work in London began to catch up. At first there was little animal experimentation, but by the late sixties the medical press was beginning to discuss the ethical dilemmas posed by physiological investigations. A distinction was drawn between procedures which yielded new information and those which merely demonstrated to students facts already beyond controversy.48 The adoption of scientific method was part of a revolution in medical practice, which increased both the workload and the prestige of the hospitals. The issue of vivisection became one of general debate with the publication in 1873 of the Handbook for the Physiological Laboratory, which was designed to assist students new to the field.49 This, and a demonstration of somewhat doubtful utility at the 1874 meeting of the British Medical Association, inflamed public opinion. An unsuccessful prosecution followed and a powerful antivivisection lobby emerged, supported by Lord Shaftesbury, Cardinal Manning and many other ecclesiastics. The movement was based upon a new Society for the Protection of Animals from Vivisection which, unlike the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, was opposed to any vivisection whatsoever. The premises of the society being in Victoria Street, it rapidly became known as the Victoria Street Society. In 1875 a royal commission was appointed, with a balanced membership, including medical scientists of renown like Thomas Huxley. The Cruelty to Animals Act was passed in 1876, but although clauses were inserted into the bill as it went through the House permitting work by bona fide investigators, the continuous agitation by the antivivisection lobby both inside and outside Parliament made the Home Office loath to grant licences under the Act. The Victoria Street Society’s campaign was of increasing concern to the medical profession. Lister himself was forced to transfer experimental work to the veterinary college at Toulouse, and antivivisectionists began to try to persuade hospital subscribers to boycott any hospital with a vivisector on its staff. The International Medical Congress of 1881, held in London, provided an opportunity to present the other side of the case, and speakers denounced the antivivisectionists as people who often engaged in blood sports while opposing those who were trying to help humanity. John Simon, by training a pathologist, said there was a grave risk to the advancement of medical science in Britain.50 When David Ferrier’s work on cerebral localisation led to his prosecution by the Society, the British Medical Association undertook his defence and the case was dismissed. The campaign was unceasing, the issue being kept in the public eye by a stream of magazine articles, pamphlets and books. In defence the medical profession formed the Association for the Advancement of Medicine by Research, which by adopting a low-profile attitude and lobbying the Home Office effectively, made it easier to obtain licences for animal work. The antivivisectionists, however, attempted to couple animal and human experimentation. Hospital finances suffered, for in the minds of many medical science became associated with vivisection. Queen Square, where David Ferrier worked, lost many thousands of pounds in this way.51, 52, 109,110. Reforming hospital administration Hospital administrators have never been greatly loved. The authorities at St Thomas’s were much criticised for lavish expenditure when the new hospital was built, and the cost of care was a perennial matter of concern. In 1857 the Statistical Society, of which William Farr was a member, published a report on the costs of the London hospitals. It showed that £300,000 was being spent annually on the sick poor of the metropolis, one tenth by the dispensaries and nine-tenths by the hospitals. Two important facts emerged: the number being relieved was greater than had previously been imagined, a total of 647,815; and there were considerable differences between the costs of the hospitals. Even allowing for faulty systems of counting patients, perhaps one in five of the population was receiving relief. And out of 14 general hospitals, three accounted for more than half of the total expenditure on the hospitals. The most recently established hospitals were the cheapest. The Lancet published the statistics of a year’s work in the hospitals. The reformers had a new cause, ‘hospital abuse’ and the ‘million a year’ who were receiving free care.

The campaign for medical reform had been underway since the eighteen thirties. Now the proper use of charitable monies and the effect of charity on the morals of the poor became issues. Hospital statistics showed the number of casualties and outpatients seen was rising, and since 1850 the rise had been very rapid indeed.53 In the words of one hospital governor: ‘We have a competition between rival charities, a fictitious demand for new institutions, a hawking about of gratuitous medical service amongst classes who do not require it, and a total number of medical charities larger than the public can be induced to support'.54. The hospitals attracted the attention of groups and associations which were seeking to improve the condition of the nation by analysing problems, debating solutions and bringing political influence to bear. These groups included the Charity Organisation Society and the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science — or the Social Science Association as it was usually referred to. The Charity Organisation Society The Charity Organisation Society was founded in 1869 to promote cooperation amongst the charitable, to prevent pauperism by promoting thrift and self-help, to make careful enquiries into those seeking assistance and, in cooperation with the poor law authorities, to give suitable help. The doctrine of the society was that the gift of money to relieve distress involved responsibility on the part of the donor for the way in which it was employed. Not for it was the promiscuous distribution of soup without thought for the effect this had on the morals of the poor. It ‘was a cardinal principle to withhold relief which was inadequate, unsuitable or which would not benefit the recipient permanently. Misguided charitable relief was seen as harmful, and the society believed that scientific principles could be established to guide the employment of charitable funds. Endowed charities came in for particular criticism, for they distributed their funds to people who met criteria laid down many years previously rather than to those who would benefit most. Following the whims of a long-deceased benefactor was considered by the Charity Organisation Society to undermine the sound work of those trying to improve the tone of the nation. It was clear from the first that a movement with such principles would be unwelcome to many. However, fortified by a firm belief in the soundness of its objectives the society was prepared to face hostility. It had many friends, quite literally, at court. Two dukes, four marquesses, and an earl were vice-presidents, as was Mr Goschen, who as president of the Poor Law Board circulated a minute urging charitable organisations to cooperate systematically with poor law guardians.55 Such was the society’s standing that it was considered quite proper for a government minister to be publicly associated with it. In 1874 the society appointed Charles Loch, a Balliol man, as its secretary. His enthusiastic idealism, strong common sense and gift of oratory were incalculable assets. His writings and speeches expounded a philosophy of charity, and the evil it could produce if administered with inadequate consideration. 56,57 The Charity Organisation Society covered the whole range of personal social services and hospital affairs were only a small part of its activities. Following its own principles of good organisation it worked through district committees whose boundaries matched those of boards of guardians. Each district committee kept a file of personal information on applicants for relief. In 1871 a medical sub-committee was established, chaired by Sir Rutherford Alcock of the Westminster Hospital, to ‘deliberate and advise on medical charities.’ The sub-committee showed a particular interest in the provident dispensary movement58 and Sir Charles Trevelyan, an ex-treasury man, showed how the society’s principles could be applied to medical charities in general. He believed that the existing system not only failed to meet current needs but ‘exercised a depressing and corrupting influence on the character of the working classes’59 To relieve pressure on hospital outpatient departments and on hospital funds he proposed a system of provident dispensaries based on the insurance principle. He said that people should be compelled to adopt habits of self-respect and industry,so that outpatient departments could be rid of medical mendicants. 51 At an early meeting the subcommittee discussed the influence which could be applied to the government to enquire into the publication of hospital and dispensary accounts. In 1874 it proceeded to examine the advantages and disadvantages of governors’ letters, and concluded that the system should be abolished as soon as public opinion was ready for the change.60 Hospital affairs were also discussed at meetings of the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science. This was founded in 1857 and met in a different city each year. One of its sections was public health.61 The Lancet rather unfairly castigated its members as a group of talkers who liked to combine food for the mind by day with food for the body in the evening, and implied that the membership consisted largely of those in positions of power, rather than of men who were ‘daily and hourly engaged in tracing the cause of disease in its habitats.62, 63 Nevertheless, over the years the membership included Bristowe, Burdett, Florence Nightingale, Farr, Holmes, John Simon and Louisa Twining. The campaign to end hospital abuse took a new turn after a meeting of the London branch of this association in January 1869. A Dr Fleetwood Buckle presented statistics supplied to him by 22 metropolitan hospitals. While those at the meeting disputed the details it was agreed that hospital statistics and accounts should be presented in a uniform shape and a committee was appointed to draw up a scheme to be recommended to hospitals. The Lancet and The Times took up the issue. The Times said: ‘The declared object of a medical charity, when abstractedly considered, appears so good and useful that it is at first sight unlikely that such charities may, in the aggregate, be sources of evil. We do not say that they are, but the fact that they encourage nearly two millions of people to be dependent upon alms is one that calls for examination into their conditions and limits of their utility.’ Necessary, though hospitals were for medical education, need they be so small? Could not 64 small ones be superseded by twelve large ones each with 400 beds? If special hospitals were unnecessarily costly and were detrimental to medical education, what could be said in favour of having four or five of the same sort? The Times suggested that patients should be charged a shilling for each attendance, and that assistant physicians and surgeons should be salaried. Some central control or organisation was wanted, perhaps a board. Inquiry must precede action and a royal commission might be a fitting way to proceed. ‘At present’ said The Times, ‘the relations which should subsist between hospitals supported by voluntary contributions, and hospitals for paupers that must be supported by the state, do not seem to be settled on any fixed or recognised principle.’ 64 The Metropolitan Counties branch of the British Medical Association summoned a meeting to discuss these issues, which were of great importance to their general practitioner members. The meeting was addressed by Mr Ernest Hart, editor of the association’s journal, but the speeches served chiefly to air views already largely accepted, that an impartial inquiry was needed to reform hospital administration and reconcile the conflicting interests of the sick poor, the subscribers, the medical students and academic staff, the hospital physicians and surgeons, general practitioners and wider public. A committee was formed to investigate and report on the whole question but it failed to agree on a report or produce recommendations.65 The Lancet revealed its own scheme for reform in which a national system of attendance on paupers and a national system of provident dispensaries would be affiliated to a national hospital system. Hospitals would be financed by a contributory sick fund and supervised by local governing boards, standards being maintained by a Ministry of Public Health. There was nothing new in the idea of state intervention; in the field of elementary education state grants-in-aid, school boards and systems of public inspection were well established. Private patient accommodation would also be provided by the hospitals. The Lancet considered the location of London’s hospitals and suggested that a convenient arrangement conducive to economy, efficiency and ease of access might consist of Guy’s, St Thomas’s, St George’s, St Mary’s and The London, with two more hospitals near Euston and Shoreditch and one other on the north side of the Thames to serve Central London. With certain exceptions the special hospitals would be swept away.66 At this point a dispute arose within St Bartholomew’s Hospital where a house physician was suspended for protesting about the administration of the outpatient department. The Lancet launched a commission to enquire into outpatient management at Great Ormond Street, St Bartholomew’s, Guy’s, the Royal Free, the Great Northern and St Thomas’s. The investigation showed that the number of patients had increased rapidly and that they were being dealt with at great speed. Sometimes senior students rather than doctors were seeing them. At some of the hospitals improvements were rapidly made.67 Following these disclosures a public meeting of the staff of the metropolitan hospitals was convened at the rooms of the Royal Medical and Chirurgical Society. After a heated debate it was decided to establish a committee to study the outpatient problem. The Fergusson committee (1870) In later years the Fergusson committee was frequently instanced as an example of a group which laboured hard, produced sensible recommendations, and altered nothing. It was chaired by Sir William Fergusson FRS Bart, Professor of Surgery at King’s College Hospital and President of the Royal College of Surgeons.68 Fergusson ‘wished to do all in his power to assist medical men attached to hospitals’. Amongst the members of his committee were Timothy Holmes, a life-long supporter of the provident dispensary movement, Ernest Hart and Spencer Wells. The committee formed subgroups which considered general hospitals, special hospitals, poor law dispensaries, and free and provident dispensaries. The committee reported that many outpatients either had trivial illnesses, or could afford to pay for care. It believed that the reform of outpatient departments depended upon improved poor law medical relief under the Metropolitan Poor Act 1867. All free dispensaries should be placed under the control of the poor law authorities to ensure that there was proper enquiry into patients’ means. To encourage a feeling of self-respect among the working classes the provident dispensary movement should be extended. To make this system work and improve the standard of clinical medical education in outpatient departments, the number attending the hospitals should be curtailed. This might be done by excluding those able to pay, and by selecting cases of particular clinical interest. The committee favoured the payment of the medical staff attending outpatients and the abolition of the system of governors’ letters. The committee did not reach a unanimous conclusion about whether patients attending the hospitals should pay a charge.69 The British Medical Journal commented on the painfully small attendance at the meeting called to endorse the report, and the apathy of the profession. The journal felt that leaflets should be printed for patients and subscribers to discourage the abuse of medical charity. The question was a simple one. Working men were increasingly well off. Should they be encouraged in habits of providence and self-reliance, or allowed to believe that they need make no provision for illness, which sooner or later was bound to affect them or their families?70, 71 The apathy of the medical profession on the issue was reflected in its response, when asked to contribute to the cost of publishing the committee’s report. A total of only 12s 6d was received. The Charity Organisation Society’s medical subcommittee invited ‘the most active’ members of Fergusson’s committee to join them and organised a conference on hospital abuse. King’s College Hospital examined its practices and, concluding that there was serious abuse, accepted the offer of the Strand branch of the Charity Organisation Society to second an officer. St Mary’s also proposed to send suspicious cases to the Charity Organisation Society offices. Other hospitals, like St George’s, thought that their outpatient departments were well managed and there was little abuse. The British Medical Association established a hospital reform committee which visited hospitals to argue its case, but on the whole the governing bodies of the hospitals were unconvinced about the need for a change of policy. Nevertheless they continued to receive unsolicited advice about the management of their affairs from Timothy Holmes and the Hospital Reform Association, which instructed them to enquire into patients’ means and cease the provision of free medicine.73 They took little notice. After 1873 the financial position of the hospitals began to deteriorate. The poor harvest of 1879 was followed by an agricultural depression lasting several years, which had a particularly grave effect on hospitals like Guy’s and St Thomas’s whose endowment income was dependent on farm rentals. They were faced with overwhelming demands for care and the tragedy of turning seriously ill people away. In April 1878 the Lord Mayor of London appealed at the Mansion House for £100,000 to support The London Hospital, but the financial darkness surrounding the hospitals grew thicker and thicker. By April 1882 the annual deficit at St George’s was £6,500, the Middlesex £10,000, University College Hospital £6,400 and The London £26,000.74 Hospitals varied in their techniques of handling the problem. St George’s recognised the importance of balancing income and expenditure. In April 1883 the hospital launched an appeal for £22,000 at Grosvenor House under royal patronage. Less than £300 was raised on the day. Simultaneously The London Hospital, which was ‘managed on the principle of administering an ever-increasing and practically unlimited amount of gratuitous medical relief, without providing in the first instance funds to pay for its maintenance’, enlisted the support of the Lord Mayor of London and a member of the royal family, held a meeting at the Mansion House, and asked for £150,000. It received nearly £40,000 in the room. The Lancet commented that if the direction in which the gifts of the charitable flowed was taken as evidence, philanthropy and intelligence were seldom to be found combined in the same individual.75 Both were excellent and much needed institutions, but St George’s was, in The Lancet’s view, more worthy of the support of the thoughtful philanthropist. At Guy’s the treasurer recorded, year by year, the diminishing income from the hospital’s estates.76 Beds were closed to restrict expenditure and by 1887 150 were out of use. Contributions were sought from the governors and their friends and a special appeal was launched. In the annual report for 1890 the treasurer stated that the hospital must in a large measure depend for its maintenance on the voluntary assistance of all classes of the community. The Hospital Saturday Fund was thanked for its contribution, noted as being larger than that of the Sunday Fund. The burden of the payment of rates was particularly resented, for the hospitals were providing free care for people who might otherwise be a charge on the guardians. Only the special hospitals seemed to be weathering the financial storms, for most of them were energetic and innovative money raisers. Payment by patients The financial problems facing the hospitals led to reconsideration of whether patients should pay, when they could, towards the cost of their care. The pros and cons of pay hospitals began to be discussed in the press. Most large cities in other countries had a hospital where one could pay for treatment, like the French Maisons de Santés. This was unusual in London, although a few hospitals, the special hospitals in particular, allowed paying patients into certain wards. The traditional principle of the voluntary hospitals was to provide free care on a charitable basis to those considered to be eligible. But some people, though fit objects for charitable care, could nevertheless make a small contribution to the hospital’s funds. Others might be able to meet all the cost. As hospital care became more effective and more desirable, the rules of the charities were debarring many who could benefit from being admitted. A pauper could be treated in an infirmary, the poor in hospital, and the wealthy in their own homes. But the middle classes, and clerks or men in the early stages of a professional career, often living in lodgings, had nowhere to turn.

In 1877 Henry Burdett, the

superintendent of the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital, began to

canvas the idea of a separate ‘pay hospital’, a concept of which The

Lancet approved.77 Supported

by men of suitable eminence, he approached the Lord Mayor of

London for permission to hold a meeting at the Mansion House.

The influential people Burdett assembled included