From Districts to Trusts

A

health care system, any health care system, is in a state of permanent

reform. I understand that annoys and upsets everybody who works in it. But it

is almost inevitable.

Kenneth Clarke in The Wisdom of the Crowd, 2013 25

The

period from the 1982 restructuring, through the Andrew Lansley reforms of

2012/3, saw a slow, progressive but massive change in the NHS. Secretaries of

State grappled with the problem of how to combine the central responsibility to

Parliament for a health service, with the need for devolution of decision

making. Financially there were intermittent crises. Socially, greater

patient/customer responsiveness was required. Clinically, until in

2020 the service was near overwhelmed by Covid-19, it was moving

from acute episodic diseases to the treatment of multiple chronic illnesses. The

development of magnetic resonance and other forms of imaging, new

pharmaceuticals increasingly based on genetic developments, rapid improvement in

cardiac surgery, in minimal access surgery and in day care changed the hospital

service. In general practice, family doctors gave up

their 24-hour responsibility and considered the way in which they might

cooperate across practices. Care in the community and integration of health and

social services were thought to provide a solution.

In

1982 the hierarchy of the NHS was clear and strict, a planning system

underpinned financial allocations and, in London as throughout

England, organisation was the same, if not in the other countries of the UK. By

2016 financial flows had changed, with the introduction of commissioning, and

care was delivered by a wide variety of trusts, some foundation ones with

greater freedom, but also by private organisations holding contracts. Indeed

whole hospitals might have been designed, built and partly managed by the

private sector, perhaps under the private finance initiative (PFI). People

received care paid for by the NHS; who provided it became less important both to

Labour and the Conservatives. Yet at the same time, quality and outcomes of

care had achieved an importance never previously seen.

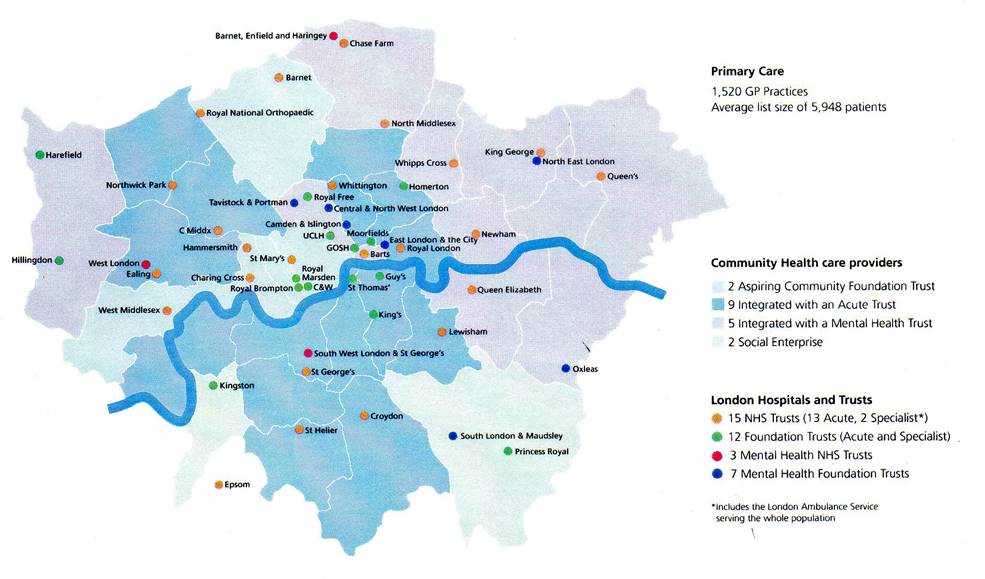

From 2006 London had, for the first time, a single strategic authority, NHS

London. When abolished in 2013, London had its own NHS England region,

one of four. Instability had been consciously introduced. New styles of

management were called for and, as the market swerved between collaboration and

competition, new forms of regulation were needed partly driven by scandals.

Politically, the earlier years were dominated by the Conservatives, then for

over a decade by Labour, then a coalition of Conservatives and Liberal Democrats

and finally a Conservative administration once more. Nationally the economy

expanded in the early eighties, but in 1989 there was a recession after

Britain’s forced departure from the Exchange Rate Mechanism. By

the mid-nineties, the economy was once more healthy, and from 2000-2008 there

was an unprecedented increase in money for the NHS until in 2007

a worldwide financial recession brought growth to an end, and in spite strenuous

efforts, the majority of trusts were in deficit.

Demography

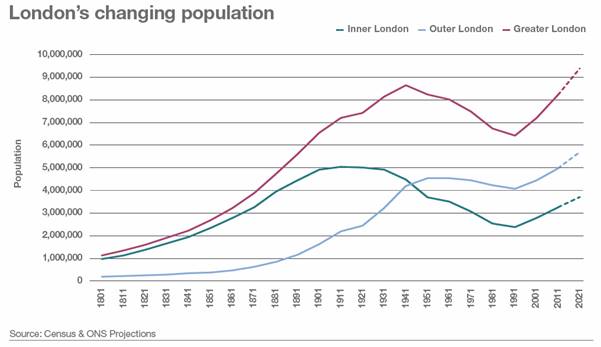

London's population was changing substantially in numbers, distribution, and

characteristics.1 From a peak of 8.6 million residents in 1939, it

fell for half a century to a low point of 6.73 million in 1988, its size 80

years earlier. After 1981 inner London grew more rapidly than outer London and

faster than the UK as a whole. By 2031 the population was expected to reach 8.8

million. In most of England the population was ageing, but in London it was

getting bigger and younger, with an increasing birth rate and a net inflow of

young adults. Docklands and the Light Railway, and building in Stratford for

the 2012 Olympics spurred regeneration in the east. There was an influx of

people from Eastern Europe as the European Community expanded. Soon the

indigenous population of London would become a minority.

|

Inner

London (millions |

Outer

London (millions) |

All

London (millions) |

|

|

1901 |

4.9 |

1.6 |

6.5 |

|

1939 |

8.6

(peak) |

||

|

1961 |

3.481 |

4.496 |

7.977 |

|

1971 |

3.060 |

4.470 |

7.529 |

|

1981 |

2.55 |

4.244 |

6.806 |

|

1991 |

2.599 |

4.23 |

6.829 |

|

2001 |

2.867 |

4.565 |

7.336 |

|

2006 |

2.954 |

4.508 |

7.559 |

|

2031 |

3.687 |

5,152 |

8.840 |

NHS

structural change

Continuous structural changes took place nationally. Key dates were

1982 Restructuring increasing district power and simplifying the planning

system

1989 Working for Patients; Conservative NHS Reform, splitting

commissioning and provision

1997 Labour’s The New NHS, Modern, Dependable, followed by a further

wave of structural change in 2000

2013 Lansley/Coalition structural changes abolishing Special Health

Authorities and producing disastrous confusion, gradually mitigated without

further legislation.

London reports.

Against the changing national background, London's services were regularly

reviewed. There was a new accent on quality, regional specialties, and primary

care, presaged by the reports of the London Health Planning Consortium. A

series of London reports, (1992 - Tomlinson 3, 1997 - Turnberg 4 and

2007 - Darzi 19) aimed for a hospital service that was smaller,

stronger and with a more substantial research base and better

infrastructure. Medical schools united, and health service mergers generally

mirrored them. In multiple reorganisations District Health Authorities

disappeared. Regional Health Authorities went as did their successor Strategic

Health Authorities. Consortia of commissioners, the London regional branch of

NHS England, and new Academic Health Science Centres replaces them as drivers of

change. Of the five UK Academic Health Science Centres identified three were in

London.

The

initial perception was that there were too many beds and too many small

specialist units, with only a small throughput of cases probably associated with

poor results. There was certainly a dearth of services in the long term sector,

for the mentally ill and the elderly. To the imperative of keeping within

budgets was added a new pressure for quality of care, fuelled by scandals of

poor care.

Underpinning the changes for much of the decade was the belief that competition

was to be welcomed, not feared, and that incentives might deliver better

performance. Change was driven by the financial climate, politically

inspired organisational restructuring and the belief that patient choice was

important.

Historically London's hospitals had ignored general practice. London seemed

unique in its failure to resolve the problems. The mobile young, a multitude of

ethnic and immigrant groups, an intelligentsia and users of drugs and alcohol

all congregated in London. Academic general practice developed late in London,

there were fewer innovative GPs and modern premises were less often to be

found. High land values, unsavoury locations and planning problems made it

almost impossible to find a good site in the right place. Recruiting young

doctors was a perennial problem. Inner city GPs were, on average, older, often

single-handed and many had trained overseas. Young doctors seldom wished to

enter such practices. ‘Better’ doctors went to greener pastures.

It

became received wisdom, without much supporting evidence, that substantial parts

of care delivered in hospital could be moved into the community. In a report

(Primary Health Care in Inner London, 1981 11) commissioned by

the London Health Planning Consortium, Donald Acheson, later Chief Medical

Officer, had provided an analysis of the problems. After the Acheson Report, it

was no longer possible to discuss health services in London without taking note

of the condition of primary care and making at least a symbolic gesture towards

the solutions of its problems. Brian Jarman wrote later than none of the

report's London-specific recommendations had been effectively

implemented. Following Acheson, attempts to improve matters included a London

Initiative Zone established after the Tomlinson Report to improve GPs' premises,

recruit a new cadre of GPs, introduce innovative approaches to old problems and

develop cost-effective care outside hospital. A review five years later showed

improvement in premises but in some areas the standards remained unacceptably

low. London still had fewer young GPs, more single-handed practices, and larger

lists. There were more practice nurses, but although primary care in the capital

was improving, it was doing so no more rapidly than elsewhere. The initiative

was terminated. The Turnberg Report (1997) again recommended support for GPs

and the need to improve recruitment and retention. It could be argued that the

pattern of general practice that worked excellently elsewhere was unsuitable for

inner cities and an alternative contract for GPs was introduced. "Personal

Medical Services" made salaried service practicable and seemed particularly

appropriate for London. After 2000, new national initiatives aimed to improve

access to the NHS, for example, walk-in centres - which were not particularly

successful. Urgent care centres were established alongside hospital A and E

units to filter off those not requiring the mostintensive facilities. The

importance of primary health care was stressed again by Darzi 19 (2007),

who wished to see the development of 150 large polyclinics from which all GPs

and the associated staff would work. In many areas, there were already plans to

provide better and larger premises, and these initiatives were promptly renamed

polyclinics.

In

general practice, family doctors gave up their 24-hour responsibility, throwing

extra strains on the hospital service, and considered the way in which they

might cooperate across practices, establishing clinical networks or federations.

Boundaries have always been significant in London hospital planning. If

hospitals were to be part of a system, they either had to be looked at in groups

or else in terms of the specialist services that they provided. Over the years

there have been discussions about whether London's hospitals should be

considered on a concentric or a radial pattern. The doughnut (with all the jam

in the middle) placed emphasis on the teaching and specialisationin the centre,

leaving the periphery alone. The alternative, the starfish (which had radial

communications and relationships), tried to relate central expertise to the

surrounding shire counties. In the late 1970s, the London Health Planning

Consortium had planned on a London-wide basis, although the implementation had

been left to the four Thames Regional Health Authorities and most took little

action. Rationalisation increased in tempo after the 1982 restructuring of the

NHS, spurred by financial pressures. After the demise of the London Health

Planning Consortium, the chairmen of the twelve teaching districts examined what

was happening and found it impossible to predict the future.

The spatial

framework of planning in London often changed, confusing and delaying

action. Sometimes the boundaries of the 4 Thames regions were used (1948 -

1994). Then there were Department regional offices (1996-2002). A five sector

scheme proposed by the Turnberg report (1997) was used, reflected in five London

SHAs (2002-2006) - North West London, North Central London, North East London,

South East London, and South West London. The five were reduced to two and then

a London-wide Strategic Health Authority (NHS London, July 2006) was introduced,

to be abolished by the Lansley reforms in 2013 in favour of a London regional

branch of the new NHS England. This appeared to follow the Turnberg five sector

approach.

National organisational changes and their London effects

1982-9 Conservative government & Working for Patients

The

General Management Function 5

NHS

management changed after a major review in 1983 by Sir Roy Griffiths, an outcome

of the industrial action of 1982 and the weakness of the 1974 restructuring. In

a memorable sentence he said, ‘if Florence Nightingalewas carrying her lamp

through the corridors of the NHS today, she would almost certainly be searching

for the people in charge.' Griffiths' recommendations included a small, strong

general management board in Whitehall, that all day-to-day decisions should be

taken in the main hospitals and clinicians should be involved more closely in

management decisions and should have a management budget and administrative

support. A general manager should be identified (regardless of discipline) at

each level and authorities should have greater freedom to organise the

management structure suited to their needs. Griffiths believed that the lack of

a clearly defined general management function was responsible for many problems

and that the development of management budgets was vital. Consensus had to go.

The government accepted the report.

1989 Working for Patients

6

The next major

organizational change took place under Mrs Thatcher and Kenneth Clarke. In 1986

twelve London hospital consultants wrote to the Times talking of the reduced

allocations and falling bed numbers.

"The inner

London population is no longer receiving an adequate medical service. The

future of the hospital medical service in London looks grim."

There were

demands for a review of the hospital and health service. What the professions

got, the Conservative's NHS Reforms, was not that for which they had been

hoping. Many of its concepts were later accepted by Labour. The basic NHS

structure had not altered greatly either during reorganisation of 1974 or

restructuring in 1982. The Conservative government repudiated consensus and

partnership with the professions in policy making, and the broadly bipartisan

approach to the NHS had ended. Among its beliefs were the importance of a sound

economy without which public services could not be funded; the view that there

was little the public sector could do that the private sector could not do

better; and that managerial inefficiency was rife throughout the public sector.

This approach was only part of a wider ideological battle about society,

industry and public services. The main ideas often attributed to Enthoven’s

Reflections on the management of the NHS, 7 were current in

radical-right circles. Working for Patients accepted many basic

principles of the NHS, central funding from taxation and largely free at the

point of usage. The idea that a major injection of funds was all that was needed

was rejected. Instead, reforming incentives and the introduction of a ‘market’

would improve productivity. The purchasing function would be separated from the

provision of services. Health authorities would concentrate on the assessment of

needs and contract for services; hospitals and trusts would provide them. A

good performance would be rewarded for money would follow the patients. The high

costs of central London, compared with the lower ones of hospitals on the

periphery, might be a problem for central hospitals.

Hospitals and

community services could apply for self-governing status. NHS hospitals were

progressively transformed into publicly owned substantially self-governing

trusts. Managerially élite hospitals had substantial freedom. The idea of

trusts had been developed with acute hospitals in mind, but applications were

received from mental illness and community services. They too saw advantages in

the freedom of action.

The

Trusts generated their revenue from contracts with districts, commissioning

agencies and GP fundholders. They needed good financial information, but the

data required to compare relative costs were poor; the necessary systems were

not in place. Many hospitals had no price list. Block contracts,

notional costs, and wild price variations were commonplace. It took much work to

sort things out. Over the first few years, there was some change in the

pattern of patient flows which had a potential to destabilise budgets, perhaps

5-10%. There had been anxiety that district purchasers would make more radical

changes, building up services in local hospitals many of which were new with

young staff and spare capacity, so avoiding high-cost hospitals in

the centre. The countervailing advantage in the centre was that a high

proportion of the medical and surgical consultants had sub-specialty expertise

making them the natural place for junior medical training.

Doctors were now employed by the trust and not the RHA, so they began to think

in a more local way. At Guy's, a hospital that had major financial problems but

wished to expand its services, clinical directorates were established under

medical control on the ‘Johns Hopkins’ model. Decisions could be taken more

rapidly, new patterns of staffing could be introduced, and services could be

improved without bureaucratic delays. Because their unit budgets were determined

by contracts with purchasers, it was easier to persuade consultants to change

their patterns of work.

The

need for hospital trusts to generate income led to visible changes.

Lilac coloured carpeting and easy chairs, smiling receptionists, a florist’s

stall bursting with blooms, a bistro coffee bar and newsagents would appear.

Trusts spent money on glossy pamphlets on their services, and logos. Acute

hospital trusts established private patient units to compete with private

hospitals and sometimes developed outreach services; community trusts looked at

hospital-type day care. The borders could blur. The boundary between the NHS and

private medicine was indistinct and the phrase ‘internal market’ seemed

increasingly inappropriate.

London Reports

There were two major planning exercises in early 1992, one by the King’s Fund

led by Virginia Beardshaw and one later that year initiated by

the government (Tomlinson 3).

1991

- The King’s Fund Commission 16

The

King’s Fund appointed a Commission in 1991 to develop a vision of services that

would make sense in the next ten years. RAWP was having a detrimental effect on

London, the RHAs were not taking a London-wide view, and there were fears that

the newly introduced internal market would disadvantage London’s hospitals. It

spent £500,000 commissioning 12 research reports and the final

document analysed the interlocking set of problems posed by health services,

medical education and research in London. It said that Londoners received a

poor deal and warned that health care in the inner-city might become

inappropriate unless there was the political will to back a strategy of

fundamental reform. The report accepted the case for a reduction in acute

services with a complementary build-up of primary health care, but did not

consider the paucity of back-up beds in nursing and residential homes that

barely existed in the metropolis. It reported that at least 5,000 beds must be

closed if the capital were to be guaranteed a good standard of health into the

next century. ‘Costs in London are not just expensive, they are extremely

expensive . . . change is inevitable . . . Inner London hospitals are top-heavy

with doctors and the rate of patients going through is slower.' While the

report indicated the direction of change needed, it did not suggest the choices

that had to be made or which sites might be closed. Attacks were mounted on its

findings because of a belief that it was working towards a pre-determined

conclusion and that some of its members had little sympathy for London or for

specialists. Virginia Bottomley, Secretary of State from April 1992 to July

1995, would have liked support for decisions she needed to take. She did not get

it.

The

Conservatives, committed to market solutions but faced with clear problems

requiring decisions, embarked on strategic planning. At the 1991 Conservative

Party conference William Waldegrave, then Secretary of State for Health,

announced a review by Sir Bernard Tomlinson, Chairman of the Northern RHA. A

safe pair of hands, he would ensure that the King's Fund did not 'run away with

the ball.' Big building projects were imminent at UCH and St Mary's and there

was no logical basis for making decisions. The Times said

that Mr Waldegrave was ‘wringing his hands’ over what should be done and needed

to be convinced that major decisions were intellectually based.

UCH/Middlesex, strongly supported by the scientific community because of the

quality of its work, wanted a new building and this might mean the closure of

other hospitals. Already expansion had been approved at Guy’s, the Chelsea and

Westminster was established and St Mary’s was being developed. The effects of

RAWP on central hospitals, in the event over-estimated, and of the internal

market, were key to the commissioning of the inquiry. However, William

Waldegrave had delayed the need to take action before an election. Those working

on the two reviews cooperated, and data was exchanged.

Tomlinson reported in October 1992.3 He emphasized

the need to improve primary and community care to national standards

and provide services for people with special needs such as the

homeless. Tomlinson argued for this, and the government provided £170 million

over six years in a ‘London Initiatives Zone’ covering about 4 million people,

where needs were great, and an innovative approach was required. Most

people under-estimated the complexities of building new and better facilities

for GPs and primary health care teams. Neither was it easy to turn a

theoretically attractive plan for the teaching hospitals and medical schools

into schemes on the ground. The money helped new projects and encouraged the

study of long-standing problems of inner London practice but the p Tomlinson

reported in October 1992.3 He emphasized the need

to improve primary and community care to national standards and provide services

for people with special needs such as the homeless. Tomlinson argued

for this and the government provided £170 million over six years in a ‘London

Initiatives Zone’ covering about 4 million people, where needs were great and an

innovative approach was required. Most people underestimated the complexities of

building new and better facilities for GPs and primary health care teams.

Neither was it easy to turn a theoretically attractive plan for the teaching

hospitals and medical schools into schemes on the ground. The money helped new

projects and encouraged the study of long-standing problems of inner London

practice but the pace of change was slow and the effect on acute hospital

services minimal.

The

Tomlinson Report foresaw a surplus of 4-5,000 beds because of the withdrawal of

inpatient flows from outside central London and the increasing efficiency with

which beds were used. The report suggested reducing the number of medical

students in London by 150. Whole hospitals should be taken out of use and the

resources redeployed to develop primary care and community services. Tomlinson

revived earlier proposals forrationalisation. UCH/Middlesex that had

become a single, powerful and scientifically

important organisation. The Middlesex site of the combined University

College/Middlesex hospitals should close and its services relocated tothe

University College Hospital site. The London Hospital for Tropical Diseases, and

the Royal National Throat, Nose and Ear, at Gray's Inn Road, would shut, and

move to the redeveloped University College Hospital There would be a single

management unit for St Bartholomew’s and The Royal London; the loss of one

hospital from among the south London hospitals of Guys’, King’s, St Thomas’ and

Lewisham, and Guy's and St Thomas's should merge on one site. The report

proposed linking 8 of the 9 London medical schools into four and associating

them with four multi-faculty colleges of the University.

The

Homerton in Hackney should take most Hackney patients currently treated at

Bart's. The Middlesex site of the combined University College/Middlesex

hospitals should close and its services relocated on the University College

Hospital site. The London Hospital for Tropical Diseases, and the Royal National

Throat, Nose, and Ear, at Gray's Inn Road, would shut, and move to the

redeveloped University College Hospital. Guy's, by London Bridge station, and

St Thomas's, a mile away opposite the Palace of Westminster should merge on one

site under a joint trust board. St Mark's Hospital, in Islington, which

specialised in the treatment of bowel diseases, would become part of the

Northwick Park district hospital complex in Harrow, Middlesex.

Charing Cross, in Hammersmith, which had the greatest excess costs, must close.

The Royal Brompton hospitals, dealing with heart and lung complaints, and the

Royal Marsden cancer hospital should be brought together on the vacated Charing

Cross site. If not, the site should be sold. St Mary's, Paddington needed to

reduce the number of its beds, and Queen Charlotte's maternity hospital

should shut, and its services moved to the Hammersmith. The capital's

postgraduate research institutions should consider ways to concentrate the

single specialty research institutes on fewer sites.

Sir

Bernard estimated that cuts in acute services and rationalisation could yield

£54m a year. There were four broad responses: the optimistic that primary and

community care could be brought up to the standards elsewhere; the realistic

accepting the recipe but gloomy about the money and the difficulties; the

despairing who doubted whether anything would be accomplished; and the reaction

at St Bartholomew’s that was to indulge in old-style emotional campaigning

against the proposals. St Bartholomew’s had come to believe its

own rhetoric, and dismissed any proposal not to its liking, however well

founded. Its campaign was given a voice by the Evening Standard in

probably the most ferocious media war ever waged against health service managers

and NHS policy, unparalleled in its unstinting aggression and partiality.

After the

unexpected Conservative victory in April 1992, the new Secretary of State

Virginia Bottomley began to take decisions although eminent men tried to bully

her. "I had all these great-uncles who died in the first war, we were taught

that when the whistle blows you get out of the trench and you walk towards the

guns. That is what I was brought up to do, to get out of the trench and walk

towards the guns."3 She redefined the NHS as the provision the

provision of care on the basis of clinical need, regardless of the ability to

pay, not by who provided the service. In February 1993 the Department of

Health's response Making London Better, 3 accepted the general

thrust of the recommendations, and the need to develop primary health care. It

provided a comprehensive blueprint for further development, some of the changes

ultimately proceeding. (*)

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE/MIDDLESEX: The hospitals should merge on one site and absorb

two of the smaller specialist hospitals, the Royal National Throat, Nose and

Ear, and the Hospital for Tropical Diseases. (*)

ST

BARTHOLOMEW'S: appraise three options - closure, merger with the Royal London

and the London Chest; or retention as a smaller specialist hospital (*)

ST

THOMAS'S and GUY'S: Merger consolidating services on one site

CHARING CROSS: A&E workload to transfer to the new Westminster and Chelsea

hospital. (*)

ROYAL BROMPTON and ROYAL MARSDEN: consider merger. Perhaps their institutes,

could form part of a new Chelsea Health Sciences Centre

QUEEN ELIZABETH: merge with the nearby Homerton (*)

ST

MARK'S: move to Northwick Park (*)

To

drive the implementation of the Tomlinson proposals, a London Implementation

Group (LIG) was formed, chaired by Tim Chessells, Chairman of North East Thames

RHA, who had direct access to Ministers. Six specialty reviews were established

to examine clinical requirements; the clinicians in the specialty under

consideration came from outside London and could be brutal when faced with the

pretensions they sometimes encountered. The reviews (1993) proposed that the

best centres should be developed, the smaller ones should be closed or merged,

and new ones established where they were needed as at St George’s where there

was a long-standing need for renal replacement therapy. Many of the

recommendations were implemented; too much was expected too fast. Some were

revised as a result of more general considerations, e.g. in

the south-east neurosurgery was not maintained at Guy's but at the

Maudsley. Several initiatives now came together making change possible. A

research review of the London postgraduate hospitals pointed to the need for a

wide range of skills including biophysics and molecular biology, and association

with general hospitals and university facilities. Medical school deans had to

play a difficult hand; most were privately supportive of the need for change and

prepared to work for it, but in public they had to take their colleagues with

them as far as possible. Trust chairmen had been appointed knowing there was a

job to be done. They and their chief executives were heavyweights who did not

fool around, and transitional funds were available to sugar the pills of change

and mergers. Ministers were far more involved than they had been in the work of

the LHPC. The Higher Education Funding Council (HEFCE), as a member of the

London Implementation Group, was involved in medical school mergers and

amalgamations, as well as through its direct links with the institutions. The

London Implementation Group closed down in April 1995, and the then two Thames

RHAs north and south of the river became responsible for co-ordinating change,

though they too were facing demise.

Guy's was in a difficult position. It had been lauded as a "Flagship" NHS

Trust, but in 1991 a black hole appeared in its finances damaging its

record. Tomlinson had suggested a merger on one site with St Thomas's, but

which site? A vicious feud broke out, the Chairman and Chief Executive of Guy's

were replaced, and their successors argued successfully for managerial

integration but a two-site solution. Guy's increasingly became the major

academic location with regional specialty work, and St Thomas's the acute

hospital with accident and emergency. In parallel, the United Medical and

Dental schools battled with academic integration. ‘During the past twenty

years,’ wrote Lord Flowers in The Times, ‘with a

few honourable exceptions every attempt to reform London medicine has been

defeated by vigorous rear-guard action on behalf of any hospital or medical

school adversely affected. The result has been that the standing of teaching and

research in London’s famed medical schools has been steadily slipping. The time

has come for the government to stand firm.’ In Making London Better 3,

Virginia Bottomley took decisions that her predecessors had been canny enough to

defer and for which her successors would be forever in her debt; she was

prepared to bell the cat, as the BMJ had put it. She narrowly escaped

defeat in Parliament and a rebellion of some senior London Tory MPs. Her reward

was the Department of National Heritage. Robert Maxwell, Secretary of the King’s

Fund, said that the creation of big medical centres across London, the main

tertiary centres of service, research and education for the future, had been

talked about for 50 years. Now it looked set to happen and would

be Mrs Bottomley’s best legacy.

Industry had been removing middle management, ‘downsizing’ and producing ‘flatter’ organisations but few foresaw that regions might be abolished. A review in 1993 of the relationship of the 14 RHAs with the centre recommended that regions should be amalgamated into eight in April 1994. London was divided in 1996 into two regions, north and south of the river. Finally regions were abolished in favour of eight regional offices of the Department of Health.

1997 - The Labour government

The

new NHS - Modern, Dependable 9

Labour took power in 1997 and Frank Dobson, the new Secretary of State, set out

Labour's initial vision in The New NHS - Modern, Dependable. The harder

edges of the internal market were softened. Fund-holding went, co-operation

replacing more extreme forms of competition. The interdependence of health and

social care, and joint programmes, were stressed. In June 1998 Frank Dobson,

decided that London would form a single NHS region and a single London Regional

Office of the NHS Executive was established in January 1999. The arguments

against such a pattern, vetoed by Bevan in 1946 and also rejected at the time of

the 1974 NHS reorganisation, were now weaker. A London region had been proposed

by Tomlinson. Change had therefore been expected and affected the boundaries of

the surrounding areas. Hospital trusts became accountable to regional

offices for their statutory duties, and to health authorities and later primary

care trusts for the services they delivered. The separation of planning from

provision and decentralization of hospital management was maintained. If

Tomlinson had been the Conservatives’ review of London, Turnberg was Labour’s.

1997 – Turnberg 4 The NHS and University Medical Schools

Until the mid-1990s it was believed that London's hospitals provided too many

acute beds and it was right to reduce their number. As London came under ever

increasing financial pressure following the Resource Allocation Working Party

Report (1976), and clinical developments speeded earlier discharge, hospitals

were closed against substantial opposition and the number of beds continued to

fall. 'Every workhouse I tried to close,' said Kenneth Clarke, 'was regarded as

a centre of clinical excellence by all the staff who worked there and all its

patrons. The most extraordinary dumps were defended by banner-waving

demonstrators.'25 Ultimately the belief that there were too

many beds became untenable. After the election Labour had faced problems with

commitments such as no hospital closures - Frank Dobson had made scurrilous

remarks about Virginia Bottomley's decisions on St Bartholomew's - an end to a

postcode lottery and the salvation of St Bartholomew's. Labour saw that health

services needed to be coordinated with changes in medical education and, perhaps

to get himself off the hook, Frank Dobson commissioned a strategic review of

inner London, increasing uncertainty just as some clarity had been obtained. Led

by Professor Sir Lesley Turnberg, it reported within months.4 It

focussed on wider strategy, recommending large scale planning for major change,

greater involvement of the public in the development of proposals and a future

focus on primary and community care. It made specific recommendations in

relation to several hospital sites. It was clear that there was great pressure

on London services, workload was rising and the number of GPs was falling.

Hospital bed numbers had fallen substantially; between 1990/1 and 1995/6 1130

acute inpatient beds had disappeared from inner London, and when geriatric,

maternity and psychiatric beds were included the loss across London as a whole

had been 9,271. Turnberg concluded that there was now no evidence that there

were more acute beds available to Londoners than the English average, taking

into account the use of London beds by non-Londoners. The subsequent NHS Plan (2000)10 accepted

that a substantial increase in capacity was needed if waiting lists were ever to

be reduced. Improvements in primary care had not been able to substitute for

reductions in secondary care. The campaigning by St Bartholomew's gave an

impression that its fate was the key decision Turnberg took, but the Royal

London Hospital was planning a massive rebuild and other important issues

included mental illness, primary care and community services, and the medical

school mergers that had health service consequences. Queen Mary's Roehampton was

also scheduled for closure.

Turnberg felt that a five sector scheme would assist planning and health

authorities should work together at sectoral level. This scenario has had a

permanent effect on health planning in London. The sectors were not unlike the

inner parts of the old Regional Health Authorities (for the shire counties had

been separated) and reflected a five sector scheme Tomlinson also had

liked. Radial organisation had been referred to in the sixties as a "starfish"

pattern. The more egalitarian term of Pizza slices was now used and within the

slices PCTs, Trusts and the educational authorities had a commonality of

interest that led them to work with each other, rather than with other slices.

Reconfiguration

A

new imperative was now emerging - rationalising/reconfiguring the hospital

system. The need to provide specialised expertise 24/7, medical staffing

problems and the restriction of the hours worked under EC legislation had

changed the criteria for defining the size a safe hospital. The progressive

increase of sub-specialties meant that rotas of consultants in all the

subspecialties could be accommodated in a large hospital but not in smaller

District General Hospitals (DGHs). Now that far more specialties were involved

in care, there had to be full cover of each to provide a 24-hour service. It was

rational to plan for fewer major hospitals, strategically placed. These might be

supported by more local facilities. National Service Frameworks developed for

clinical specialties outlined clinical networks of hospitals varying in their

sophistication. Reports of the BMA, Royal College of Physicians (RCP) and Royal

College of Surgeons of England echoed the earlier thinking of the Bonham-Carter

Report (1969), suggesting that a single general hospital now should serve

populations of not less 500,000.14 Under pressure

to improve the volume and quality of services without higher costs, some trusts,

for example the Central Middlesex, introduced process re-engineering. If the

stages in the delivery of care were examined, was there a better way of

designing the system? Given better drugs and anaesthetics allowing more speedy

recovery, state-of-the-art diagnostics and imaging, minimum intervention

techniques and better information systems, could any stages be omitted, or be

arranged more economically to save the time and money of both patients and

staff? When financial pressures grew, and problems of quality emerged, trusts

increasingly considered that merger would help to solve problems. Progressively

these took place.

A

related problem was the provision of effective emergency care when most

consultants were super-specialists. The RCP said half of the hospitals it

surveyed had adopted an emergency admission ward, perhaps of 20 beds, with a

system of assigning patients to specialist units. The RCP suggested that Acute

Medicine was a separate specialty, required by each hospital taking acute

admissions.

Hospital developent in the five Turnberg sectors

New hospitals planned in the 1970s had opened in the 1980s, for example, the Newham Hospital (1983) and the Homerton in Hackney (1986). Development was often supported by the Private Finance Initiative (PFI), and major changes took place in each of the five 'Turnberg' sectors adopted as the boundaries for managerial bodies. The problems with PFI were the inflexibility once the building had been opened and the financial costs that stretched way into the future and sometimes closed off other opportunities.

From 2002 until

2006 London had five Strategic Health Authorities and from then until 2012 a

single one, NHS London, with an overview of the entire metropolis.

North East London

In the North East

decisions were most needed about The Royal London and St Bartholomew's, Queen

Mary College and the medical schools of the two hospitals. These two hospitals

and their staff had long-standingdivergences and a deep distrust of each

other. As part of the Conservatives' NHS reforms (1990), the idea of

self-governing hospital trusts within the NHS was introduced, and Bart’s was

planning to set up such a Trust when its independent future was called into

question by the Tomlinson Report which did not see Bart’s as a viable hospital

and recommended its closure. The Government’s response in 1993 supporting

Tomlinson gave three options for Bart’s: closure, retention as a small

specialist hospital, or merger with the Royal London Hospital and the London

Chest Hospital. This sparked an intense public debate and a campaign to save the

hospital on its Smithfield site. In April 1994 a Trust was formed,

incorporating the three hospitals. Turnberg had supported the case for

the redevelopment of a 900 bed secondary and tertiary care hospital

in Whitechapel while maintaining some tertiary services at Smithfield, mainly

cardiac and cancer services. A billion pound PFI development began, the

financial cost of which overhung the trust and prevented it achieving foundation

trust status. Later mergers were encouraged, culminating in 2012 in the creation

of a huge trust, Barts Health, uniting St Bartholomew's, The Royal London,

Newham and Whipps Cross hospitals. Its management insisted that major savings

could be made, but they proved illusory. By 2015 there was an annual

deficit of £93 million, a CQC report revealed poor nursing standards

particularly at Whipps, and the trust was put into special measures. An

agreement was made with UCLH to exchange cardiac services for cancer, leaving

Barts to concentrate on the former.

New building was

undertaken at Whipps Cross and Newham General (an Ambulatory Care and

Diagnostics Unit and an adult mental illness unit). A new Queen’s Hospital in

Romford brought together the services previously run at Oldchurch and Harold

Wood hospitals; built under the Private Finance Initiative, it opened in 2006,

complementing the rebuilt St George's Hospital Ilford where lower risk

and midwife-led maternity care was provided. It was the second of two huge

hospitals in north-east London.

North Central London

The

Department of Health had supported merger discussion between the medical schools

of UCH and the Middlesex Hospital, two organisations with a similar ethos, and

the previous boundary between North East Thames and North West Thames was moved

so that the districts containing these hospitals united in 1982 as Bloomsbury.

The Eastman Dental Hospital had special health authority status but in 1996

joined UCLH. The Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital (1888) became part of UCLH

in 1994. The Hospital for Tropical Diseases, the home for the London School of

Tropical Medicine, moved first to St Pancras Hospital and then to the main part

UCLH. The National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery joined in 1996, the

Institute of Neurology affiliating to UCL. The Royal London Homeopathic Hospital

joined the group in April 2002.

Turnberg supported the proposal for capital development and ground was broken in 1999 for a £422 million private finance initiative that opened in 2005 uniting most of the University College London Hospitals on a single site. The old Middlesex Hospital site was sold off profitably for redevelopment as flats, gaining the Trust £175 million. With its new development commissioned, and its financial situation sound, the Trust rebuilt its obstetric hospital (the EGA wing) and cancer unit and looked to bring other hospitals, including postgraduate teaching hospitals, onto its site, e.g. the transfer of the Royal National Throat Nose and Ear Hospital from The Royal Free to UCLH.

Substantial development was taking place elsewhere. The first phase of a new Barnet General Hospital opened in 1997. A major development took place at the Whittington. At Chase Farm Hospital, a new surgical wing and Treatment Centre was built, and the North Middlesex was redeveloped with a new Emergency Care Centre, Diagnostic and Treatment Centre, and an Acute and Critical Care Centre.

A world-class medical science centre for London was developed by a partnership of Britain’s biggest funders of clinical research, the Medical Research Council (MRC) National Institute for Medical Research, the Wellcome Trust, Cancer Research UK and University College, London (UCL). A £350 million scheme went forward on a 3½ acre site near the British Library and St Pancras station. The Francis Crick Institute was the largest laboratory of its kind in the world, accommodating 1,500 leading researchers in different fields In 2011 Kings College and Imperial signalled their intention to associate with it.

North West London

Centrally the sector contained the Hammersmith, Queen Charlotte’s, Chelsea Hospital for Women, Charing Cross and, nearby St Mary’s, the Chelsea and Westminster and two specialist hospitals, the Royal Marsden and the Royal Brompton. It came to be dominated by Imperial College. In 1984 the medical schools of Charing Cross and Westminster hospitals united, and in the next year, the districts in which they were situated were merged into one authority, Riverside District Health Authority, with plans to rebuild and reduce the number of hospitals to two. Brent and Paddington District Health Authorities 'huddled together for strength and warmth,’ in the words of the district manager. In 1988 Parkside Health Authority was created, uniting St Mary’s and the Central Middlesex, leaving St Charles’ as a non-acute community hospital. Hospital planning involved the part-rebuilding of St Mary’s and rebuilding the Central Middlesex, the first phase being a pioneering ambulatory care centre. The new Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, which enabled the closure of five separate hospitals, opened in 1993. The Hammersmith/Queen Charlotte's new maternity facility opened in 2003.

The Turnberg report called for more rational distribution of specialist services in North West London. The outcome was the Paddington Health Campus project, a variant of the proposals in the Pickering Report of the 1960s to be funded by PFI. It would bring together Royal Brompton & Harefield NHS Trust, St. Mary's NHS Trust, Imperial College's National Heart and Lung Institute and North West London’s specialist children's services to one site in Paddington. The Business Case was approved by the Department of Health in 2001, but the cost steadily escalated until it was clear that it was not viable. It was cancelled in 2005.

In

the early 1990s the Medical Research Council (MRC), under financial pressure,

decided to pull out of its Northwick Park Clinical Research Centre and

concentrate at the Hammersmith Hospital. Northwick Park had been bought by

Charing Cross Hospital in 1944 to allow it to relocate from the centre.

Ultimately it had became a colocation of research and a district general

hospital that had a "normal" case-mix. Perhaps the idea of this association was

flawed; science grafted into an unreceptive environment at a district general

hospital where there were suspicions that patents would be "experimented

upon.” Perhaps the decision was partly the result of forceful personalities and

power politics.

This withdrawal freed modern accommodation and research space. A small specialist hospital concerned with coloproctology, St Marks, needed to move from its poor accommodation in City Road. St Marks had the foresight torealise that it had more to lose than gain from a merger with Barts and grasped the alternative, Northwick Park, with enthusiasm. Relocation in 1995 provided immediate access to intensive care, theatres and state-of-the-artimaging and service departments. St Marks had its own front door, clinical directorate and all the advantages of association with a busy district general hospital. Organisationally there was amalgamation within the North West London Hospitals NHS Trust incorporating Northwick Park & St Mark's and hospitals in Harrow, & the Central Middlesex.

The Royal Brompton & Harefield NHS Trust was established in April 1998 based on two sites, one in central London and one in Middlesex. The Trust provided services for all age groups from infancy to old age and associated with its multi-faculty university partner Imperial College School of Medicine within which was the National Heart and Lung Institute. Turnberg supported the approach to collaboration in the rationalization of services that was being undertaken by the hospital trusts and Imperial College. In 2007 under the aegis of Imperial College, it was proposed to bond the Hammersmith Hospital and St Mary's to create an Academic Health Sciences Centre, merging units such as renal medicine, and making it easier to bring cutting edge research earlier into clinical practice. This was accredited in March 2009.

In a

collaborative exercise, the eight CCGs took forward an earlier Darzi era

exercise, 'Shaping a healthier future' (2012) that aimed to

provide better care in the community. Its proposals to downgrade some A & E

Departments including Hammersmith and Charing Cross aroused opposition.

South West London

In south west London the position of St George’s was secure, and the plans to relocate the Atkinson Morley Hospital to the St George's site, and further developments there, were supported by Turnberg. The neuroscience and cardiac centre, the Atkinson Morley Wing, opened in October 2003

South East London

In

southeast London, Turnberg said that the merger of the Guys’ and St Thomas’ had

allowed the development of proposals for rationalizing services across the two

sites. There was protracted discussion and much in-fighting about the future,

whether one or the other site should close, where the accident and emergency

department should be situated, and where specialised services should be

concentrated. If these two hospitals agreed on anything, it was that King's

College Hospital was subordinate. Ultimately the A & E Department went to St.

Thomas’ because ambulance access was far better. There had also

been discussion about the distribution ofspecialised services between St

Thomas', Guy's and King's College Hospital. A new wing at King's College

Hospital opened in 2003, and a new Children's Unit was planned.

Turnberg examined redevelopment of acute services in Bexley and Greenwich, and supported the redevelopment of Queen Elizabeth Hospital to replace services at Greenwich, built under PFI at the cost of £93M. This involved the redevelopment of the former military hospital including the design, construction and financing of new buildings, the refurbishment of existing ones and the maintenance and operation of the entire hospital. Both it and Bromley soon had large deficits because of the irreducible costs of their whole hospital PFI schemes.

Since the time of the Royal Commission on Medical Education (1968) academic mergers had been proposed. The earlier Todd pairs differed substantially from the pattern later implemented.

|

St

Bartholomew's Medical College |

The

London Hospital Medical College |

Queen

Mary College |

|

University College Medical School |

Royal

Free Hospital School of Medicine |

University College |

|

St Mary's

Hospital Medical School |

Middlesex

Hospital Medical School |

|

|

Westminster Medical School |

Charing

Cross Hospital Medical School |

Imperial

College |

|

Guy's

Hospital Medical School |

King's

College Hospital Medical School |

King's

College |

|

St

Thomas's Hospital Medical School |

St

George's Hospital Medical School |

(Kingston) |

Todd pairs

St Bartholomew’s Medical College and The London Hospital Medical College;

University College Hospital Medical School with the Royal Free Hospital School of Medicine;

St Mary’s Hospital Medical School with the Middlesex Hospital Medical School;

Guy’s Hospital Medical School with King’s College Hospital Medical School;

Westminster Medical School with Charing Cross Hospital Medical School;

St Thomas’s Hospital Medical School with St George’s Hospital Medical School.

Final Mergers

Imperial College

Westminster Medical School

Charing Cross Hospital Medical School

St Mary's Hospital Medical School

Queen Mary College

St Bartholomew’s Medical College

The London Hospital Medical School;

Kings College

Guy's Hospital Medical School

King's College Hospital Medical School

St Thomas's Hospital Medical School

University College London Hospitals

University College

University College Medical School

Royal Free Hospital School of Medicine

Middlesex Hospital Medical School

St Georges

---------------------------------------------------------

Queen

Mary's

wished for a medical faculty, but was in a financially weak situation, as were

the two medical schools involved, St Bartholomew's and The Royal London. There

were substantial objections to amalgamation from both the medical schools, and

the merger in 1995 as Bart's and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry,

the medical faculty of Queen Mary University of London, was not a happy

one. Bart's and the Royal London had everything one could desire regarding a

local population, but the association with QMC, comparatively weak as a research

institution, did them no favours and the QMC and the two medical schools

associated with UCL Partners.

University College London

University College/Middlesex schools merged in 1987. The Institute of Child

Health became part of UCL in 1996 & the Royal Free and University College

Medical School was formed in 1998. University College London Hospitals while

having only small local catchments had substantial financial assets and an ideal

academic location next to UCL, perhaps the strongest research base in London. As

UCL Partners, it was selected as a National Biomedical Research Centre, in 2008

comprising UCL with Great Ormond Street, Moorfields Eye Hospital, The

Royal Free, and University College London Hospitals. New "partners" steadily

joined. As “London's leading health research powerhouse" it focussed on ten

areas of research which posed a major health challenge, e.g. children's health,

cancer and women's health. Though the medical schools merged, the Royal Free

Hospital remained under separate NHS management.

Imperial and UCL discussed a merger but decided it was in the interests of

neither side. However, the discussions divided the London medical schools into

two camps, Imperial College and UCL neither of which were supportive of the

concept of London University, and the other three. In 2005 UCL gained

independent degree-awarding powers from the Privy Council. Students registering

after 2007 had a UCL degree. Such moves, covering all subjects and not solely

medicine, tended to undermine London University.

Imperial College

Imperial College gained a medical school by merger with St Mary’s Medical School

in 1988. Its Faculty of Medicine was formed in 1997 by the merger of St Mary's

Medical School with Charing Cross and Westminster Medical School, the Royal

Postgraduate Medical School and the National Heart and Lung Institute. In 1988

the Royal Postgraduate Medical School had merged with the Institute of

Obstetrics & Gynaecology and also became part of the Imperial College School of

Medicine. The National Heart and Lung Institute situated next to the Royal

Brompton Hospital became part of Imperial College in 1995 and part of Imperial

College School of Medicine in 1997. Secure in its prestige and size, Imperial

took a firm line with the medical schools that were now an intrinsic part of it,

and with the hospitals to which they related. In 2007 St Mary's Hospital Trust,

The Hammersmith HospitalsTrust and Imperial College united to become the

Imperial College Health Care Trust, and this was selected as one of five

National Biomedical Research Centres. In 2003 it was given the power to award

its own degrees but did not immediately use it.

Imperial thought that globally there was only room for 5-6 major biomedical

research and teaching centres, perhaps two in the USA, one in the Far East and

two in Europe. Imperial considered itself the natural premier leaguecentre in

the UK. The Medical Faculty ethos was that of Imperial College, scientific based

and of the highest standard. There was a thorough reorganization to develop an

integrated Faculty, one organisation using the same letterheads The attempt to

bring the NHS and the academic side together as a single body did not work. The

huge problems of old buildings and financial deficits proved an excessive burden

on top management.

King's College

The

United Medical and Dental Schools (UMDS) of Guy's and St Thomas' was formed in

1982 and King's College London School of Medicine at Guy's, King's and St

Thomas' Hospital (earlier the GKT School) in April 1998. KCL, associated with

such powerful hospitals, gave UMDS room for manoeuvre. Internally there were

power struggles on both the service and the academic sides to determine the

future pattern of service. From 2007 students registered with King's were

awarded a King's degree, rather than one from the University of London. In

March 2009 King's Partners became accredited an Academic Health Sciences Centre

and made rapid progress to become a major player.

St

George’s

St

George's, far from the centre of London and with no substantial university link,

was not in the same league. It maintained an independent position within the

University of London but later established links with Kingston University

There were now four university centres, each related to a multi-faculty college,

plus St George’s. The postgraduate institutes were finally brought within the

fold, as proposed by Sir George Pickering in 1962.18 Within this

structure, once the colleges became directly funded by the Higher Education

Funding Council for England (the successor in 1993 to the University Funding

Council) the University of London had to accept the realities of local

ambitions, including the individual right to grant degrees. The colleges had

gained financial and managerial autonomy, UCL, Queen Mary, Kings and Imperial

being separately identified from 1993/4 and St George's two years later. The

University maintained a coordinating group of the medical faculties to discuss

strategy for mutual benefit but each college took a different approach to the

integration of medical schools within their fief.

The

replacement of Frank Dobson in 1999 as Secretary of State for Health by Alan

Milburn heralded further change. Milburn wished it to be fast and over a broad

front. Labour's second major health policy document, the NHS Plan, was

issued in July 200010 with four main themes, increasing

capacity, setting standards and targets, supervision of the way the NHS

delivered services, and 'partnership'. There was no specific London

agenda. Substantial progress was achieved in terms of waiting times and waiting

lists. Milburn’s policies involved a greater role for the private sector, for

example in the private finance initiative and independent treatment centres,

radical changes in funding with the introduction of tariffs and Payment by

Results, and Foundation Hospital Trusts with greater freedoms.

Trusts and Foundation Trusts (FTs)

In

July 2002 it was proposed that acute hospital trusts that had performed

well could apply to be "NHS foundation trusts". These would have greater

freedom in terms of management, closer links to their community and greater

local financial control. Authorisation as a FT was hard to obtain as the trust

had to meet high standards of financial security and governance

excellence. Nevertheless three London hospitals appeared in the first wave in

2004, Moorfields, the Royal Marsden and the Homerton. Later UCH, King's College

Hospital, the Royal Brompton and Harefield, and Guy's/St Thomas' also became

FTs. The Royal Free became one in 2011 and Kingston in 2012. Compared with the

rest of England fewer London hospitals became FTs. In many cases there were

financial problems, often relating to a debt overhang from developments under

the private finance initiative as in the case of the Royal London Hospital and

hospitals in South London. The trusts of the West Middlesex and Barnet/Chase

Farm sought association with existing FTs.

NHS

Foundation Trusts differed from existing NHS Trusts in key ways for they had the

freedom to decide at a local level how to meet their obligations; they were not

under the supervision of the special health authority; they had an individual

constitution that made them accountable to local people, who could become

members; and governors who could hold the board to account and, indeed, appoint

and sack the Chair

They were authorised and regulated by Monitor which kept a careful eye on

financial risks, and could provide new services and develop their facilities

from their own resources as they wished. For example, the Homerton successfully

bid to provide community nursing services to its area. If an FT sold land, it

could keep the proceeds for re-development. University College Hospital, also

an FT, sold the site of the old Middlesex Hospital for over £175 million, which

greatly assisted its redevelopment. Their revenue came largely from contracts

with the local ‘purchaser’ for which they competed with other trusts.

New patterns of hospital

medicine in London.

The NHS

Plan's structural reorganisation took place on 1

April 2002, "devolution day." At that point, there

were 28 Strategic Health Authorities.,with five for London. New

factors began to drive changes in hospital medicine in London, far more than

elsewhere. Increasingly services were planned across and between

hospitals and trusts, not merely within them. Services might be

provided more effectively in larger units, perhaps by hospital mergers

reflecting changes in the pattern of London medical schools, and there was a

drive to reconfigure services by clinical outcomes as in heart

disease, trauma and stroke

Organisational change continued in London. In 2004

Ministers said 'the unique nature and scale of health service issues facing the

capital might point to a single organisation to oversee service

development.' Following the Government report Commissioning a

Patient-led NHS (Department of Health, 2005), a single SHA was

established in London, though the PCTs that were largely coterminous with

boroughs were left unchanged.

NHS

London (SHA) and the Darzi Reports

NHS

London covered an area coterminous with the local government office region and

was established in July 2006. It was closed as a result of

the Health and Social Care Act 2012 on 31 March 2013. It brought together 5

SHAS, North West London, North Central London, North East London, South East

London, and South West London. It was, therefore, the

nearest that London had ever had to a "Central Hospital Board for London,"

providing strategic leadership for all of the health services in

the capital and with responsibility for the performance of 31 primary care

trusts. It had less responsibility for 16 self-governing

foundation trusts. NHS London was chaired in turn by George Greener, and after

his resignation in September 2008 by Sir Richard Sykes, previously chief

executive of GlaxoSmith-Kline. Sykes resigned as Chair in May

2010. NHS London had responsibility for those trusts that were not

Foundation trusts, for example, south London hospitals and Barts

and the London, which involved substantial firefighting, but also the formation

of a more strategic view of London health services.

Trouble shooting

At

the time of its establishment, financial growth had never been greater, but

this ended with the economic downturn. Trusts in south east London

had long-standing financial problems, recording annual deficits every year since

2004/2005 from the unaffordable and irreducible costs of its whole hospital PFI

schemes, 16% of their income. Cost-improvement schemes could not restore

financial health without risking the quality and capacity of services. In 2005 a

major review taking 5 years was established (A Picture of Health),

covering Queen Elizabeth, Woolwich and Bromley Hospitals, Queen Mary Sidcup and

Lewisham. The SHA would have liked to have examined all services

in south east London simultaneously, but this proved too difficult. The

final proposal was a large reduction in medical and acute bed capacity at the

Queen Mary’s Sidcup site with the closure of 284 acute beds and the cessation of

emergency admissions. To facilitate service changes a single

merged trust was established to cover three hospitals in 2009 with a total

combined debt of £149m. The merger was a financial failure, and the

Care Quality Commission found the trust was not complying with some standards of

safety and quality.

Strategy

Perhaps the SHA's most important action was, while Sir David Nicholson was chief

executive, to commission a clinician, Professor Sir Ara Darzi, to review

London's health care system. Darzi, intelligent, hardworking and

alert to trends had extensive support both in back office terms and from senior

clinicians. Legitimacy was established through the clinical leadership with an

extensive consultation programme, and by selecting a few priorities

to be tackled properly rather than trying to do everything. The

three priorities were stroke, trauma, and the

polyclinic programme. The course and outcome of this programme were subsequently

reviewed by its key officers.22 Darzi’s first

report The Case for Change (March 2007) argued

that the current system was wrong because it could not handle

health inequalities, patients' expectations, the need to centralise specialised care,

the relationship with academic medicine or give value for money. A

Framework for Action was published in July 2007, days after

Darzi’s ennoblement and his appointment by Gordon Brown as a junior health

minister in the Lords.

Darzi was one of the "goats" in Brown's "government of all talents”, and

he came to believe that his appointment as a Labour Minister turned people

against his report, though it was the product of many hands including

McKinsey’s.25 It recommended 5 principles, an individual

focus on patients' needs, services local where possible and centralised where

necessary, focus on health inequalities, prevention rather than cure and truly

integrated care. Technical groups had looked at population trends, e.g. the

population expansion in the "Thames Gateway", and the likely health

problems in London over the coming years. Clinical working groups

considered appropriate policies for care and the care pathways best suited to

differing groups of patients. Hospitals might be classified as

local hospitals, elective centres with high throughput, major acute

hospitals handling complex work, specialist hospitals, and academic

health science centres.

Brilliant in conception, but according to the Guardian a

recipe for turbulence, it was a blueprint for a radically different NHS. Darzi

envisaged that London primary care would be provided by 150 polyclinics,

handling much work previously undertaken in hospitals. Some large practices

already provided extensive facilities but the inclusion of imaging, consultant

outpatient sessions, and minor surgery would require much

investment. The number of major acute hospitals would be cut by more than a

half, some being restricted largely to cold surgery. There might

be some 12 specialist hospitals and 8-16 major acute hospitals. Patients

in emergencies would be admitted to the hospital best suited to their needs;

near or far. Services for the mentally ill and long-term conditions

needed improvement, and the report was fleshed out with reports of

working parties, for example on maternity services.

For maternity, a

tiered system was proposed according to the clinical and social

need of home delivery, midwife-run maternity units some on a

hospital campus, and full-scale obstetrician round the clock

hospital units. Darzi seemed to believe that the health service would be rebuilt

starting from scratch. The costings provided by McKinsey's

attracted significant criticism. Major savings depended on the

ability to transfer services into the community, but some polyclinic schemes

seemed lavish and were likely to cost and not to save money. Darzi accepted that

the plan had a long timescale and was confident that he could take others with him, but

this was only partly true. He wished his concepts to influence national thinking

particularly on quality, but he offended some by offering instant solutions to

problems with which people had wrestled for years. The SHA went to publicconsultation, and

a bare majority accepted most of the proposals. A joint committee of primary

care trusts (PCTs) accepted the proposals in June 2008.

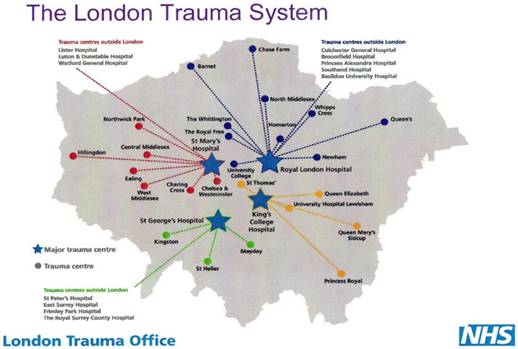

Trauma and Stroke reconfiguration

NHS London hosted Healthcare for London, a transient organisation paid for by the 31 PCTs to encourage planning of the most complex services London wide. Already heart attacks had been centred on four key hospitals. From 2006 NHS London consulted on and implemented reconfiguration of major trauma and acute stroke units. It sponsored the work that established a ‘case for change’; usually led by a clinician from the field and a steering group

reviewing the evidence. This was not always hard or absolute but

in general suggested that the more acentre did, the better they

were at it. Economic arguments were not paramount. The

decision about how many centres there would lie largely

with NHS London and the expert group and might be contentious. Similarly,

the expert group decided on the criteria by which applicant trusts would be

judged for centre status. Trusts submitted their bids, NHS London

evaluated them and once decided, the commissioning process was used to cement

arrangements. Against much opposition but usually with strong clinical support

specialist care was centralised. Many opponents of the proposals

were converted. In February 2009 eight hyperacute stroke units (HASUs) and four

trauma units were established. As a result of stroke

reconfiguration, virtually all patients who would benefit from thrombolysis got

it (18%), three times more than in the country as a whole, saving some 400 lives

a year. The HASUs were The Royal London Hospital, St George’s

Hospital, King’s College Hospital, Northwick Park Hospital,

Charing Cross Hospital, University College Hospital, The Princess Royal

University Hospital and Queen’s Hospital Romford supported by 24 stroke units

where patients would continue their recovery.

Post Darzi Reconfiguration in London

To

aid reconfiguration, in 2009 the Primary Care Trusts created five subgroups,

three north and two south of the Thames later followed by more formal

merger of the PCTs. Reconfiguration proposals were developed in North East

London and North West London (the Barnet, Enfield and Haringey

Clinical Strategy) but stalled. So did the strategy for the south west, Healthcare

for South West London. A delay imposed by Andrew Lansley

on taking office as Secretary of State for Health provided opponents of local

change with ammunition. The polyclinic programme,

itself essentially based on proposals already in hand, was ended but the primary

care trusts and their successor clinical commissioning groups pressed on with

rational developments under the banner of integrated care to improve services

for the frail elderly, with its increasing incidence of long-term problems. Evaluation showed

little evidence that the polyclinic programme had

improved service development, access, quality of care and patient experience,

and it had not generated significant cost savings. Clinical

pressure continued to ensure service transformation in cardiovascular, cancer,

mental health, maternity and neonatal intensive care and paediatric services.

A major reconfiguration in North West London, Shaping a

Healthier Future, was approved, enabling the closure of A and E at Charing

Cross, Central Middlesex Hospital, and Ealing in October 2013.

Biomedical Research

Centres (BRCs) and Academic Health Science Centres (AHSCs)

Since the time of William Osler and the Flexner report a century previously there had been recognition that service, teaching and research were mutually supportive. Driven from a research standpoint by Dame Sally Davies, the UK government recognised the economic, financial and clinical advantages of backing medical developments, research leading to better treatment. The example of major biomedical research centres in the USA, which had spearheaded clinical development, led to the establishment of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and consideration of which centres should be supported to encourage "translational research". A panel of international experts chose centres in open competition as world class in research. In December 2006 Patricia Hewitt, the Secretary of State, announced five multispecialty trusts that would be supported, three in London (Kings, UCLH and Imperial) plus Oxford and Cambridge, and a further six in particular clinical fields. NHS research moneys went preferentially to these power houses of translational research.

2010. The Coalition and the Health and Social Care Act

Labour was defeated in the 2010 election and the new Secretary of State, Andrew

Lansley, arrived with further proposals for reorganisation that he

had published while in opposition. Lansley was distrustful of

central planning. He immediately moved to embargo proposed reconfigurations,

imposing new criteria such as local support from the public and general

practitioners. Because the London SHA had been in advance of other

authorities, it was particularly affected by this decision and important

strategic plans were placed at risk. The Chair, Sir Richard Sykes,

previously chief executive of GlaxoSmith-Kline, resigned believing that the

delay was driven politically and not by logic. Many of the

reconfiguration proposals such as those in North East London had emerged from a

long process of clinical involvement and public consultation. Others, as at